Chapel House, Hamilton, NY, USA

By Kevin Trainor

Figure 1: Exterior view of Chapel House; chapel on left and house on right (photo by Kevin Trainor)

Chapel House, an interreligious retreat center at Colgate University in Hamilton, NY, opened in 1959. Its genesis was the result of an extended collaboration between Professor Kenneth Morgan (1908-2011), a faculty member in Colgate’s Philosophy and Religion Department, and an anonymous donor who provided initial funding for the creation of the center along with endowing Colgate’s Fund for the Study of the Great Religions of the World [1].

In contrast to most of the other collections profiled on this website, the Chapel House collections were intrinsic to the facility’s conceptual and architectural plan from its inception. The collections are currently comprised of more than 3000 catalogued books in the library, thousands of musical recordings available for listening in the music room (initially records, later supplemented with cassette tapes, CDs, and digital recordings), and dozens of paintings, images, and ritual objects installed throughout the complex with which visitors can interact, keyed to a comprehensive guide that contextualizes each object.

Chapel House is also distinctive in its lack of direct affiliation with a specific religious tradition or community. In most cases profiled in “Gods’ Collections,” religious shrines or “temples,” which were centered on practices oriented toward the ideals and behavioral norms of particular religious traditions, gradually accumulated valued objects through donations or patronage [2]. In contrast, the original conception of Chapel House was from the beginning directly dependent upon the academic category of religion, an orientation consonant with Morgan’s faculty appointment in Colgate’s Department of Philosophy and Religion [3]. As stated in their information brochure, the center “welcomes anyone of any faith—or none—who wishes to take the initiative in seeking deeper religious insight through the study of religious writings, or religious art, or religious music, or through the practice of religious disciplines” [4].

Given the intentional integration of collected objects into interior spaces designed to facilitate use of them and support religious practice, Chapel House is in some respects analogous to a temple despite not being rooted in a particular religious tradition. While the center offers no formal program of religious instruction or practice [5], it was designed as a kind of spiritual or religious laboratory for furthering the personal development of those who come there. The center’s emphasis on individual guests’ motivations and experiences, including those who do not self-identify as religious, evokes the modern category of spirituality; at the same time, the center also emphasizes the importance of a diversity of historical religious traditions, manifested through texts, music, art, and artifacts, in the ways that guests pursue their individual interests. In Morgan’s words:

This experiment is based on the premise that although we can teach courses about religion, we cannot teach religion itself, for religion is a personal experience. Chapel House is to be a place where one can practice the personal disciplines of meditation, prayer, and the study of religion; it will provide an opportunity to experiment with religious disciplines, to seek for new insights in religion, and to break away from the pressures of everyday living to gain a new perspective on oneself and one's community [6].

This experiment was grounded in Morgan’s own experiences of prayer and meditation in India during a break from his graduate studies at Harvard from 1935-36 [7]. His idea of creating a place in the U.S. that supported these disciplines found common cause in the 1950s with the primary donor’s religious interests, informed by her engagement with American Theosophy and Protestant Episcopal Christianity. As stated in the original donor’s Deed of Gift, Chapel House was created to support “personal religious devotion through meditation, prayer, the study of devotional literature and religious art and music, and such other appropriate means as may be devised to help people to recognize their need for personal religious disciplines and to learn the ways in which men have been able to increase their awareness of God” [8].

Figure 2: Entrance foyer with stairway on left to guest rooms and adjoining director’s office on right; Alfeo Faggi’s sculpture, “Silence,” is on pedestal at top of stairs (photo by Kevin Trainor)

The donor imposed two major stipulations: that her gift would remain anonymous and that the architectural design had to receive her approval, a daunting task since she had a troubled history with architects and was dismissive of modernist art and architecture. The primary architect was Walter Severinghaus, a senior partner in the New York office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), who was at that time also the senior project director of SOM’s Chase Manhattan Plaza project in New York (1957-64), a major work of modernist architecture in the International Style. Severinghaus was willing to undertake the design of such a modest structure because he and Morgan were college friends [9]. Morgan and Severinghaus discussed every aspect of Chapel House’s design, and SOM designers were responsible for choosing the site, the design of all the furnishings, and the landscaping [10]. When the plans were completed in 1958, Morgan, Severinghaus, and Colgate’s president Everett Case traveled to the donor’s home with a detailed building model and succeeded in gaining her grudging approval; she died before construction was completed in 1959 [11].

Nicholas Adams, an architectural historian who has written an extended history of SOM, suggests that Severinghaus’s Chapel House design in some respects exemplifies the “continuity of SOM’s practice” and its distinctive design ethos at that time, which was marked by a highly collaborative, integrated approach [12]. In the 1950s, modernist forms were increasingly adopted in religious architecture, though there are few examples of inter-religious structures. Adams suggests Eero Saarinen’s MIT Chapel as a possible influence [13], as well as domestic architecture by Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohe, concluding that “Chapel House was a significant contribution to modern religious building at a time of crisis in the typology” [14]. The simplicity and clean lines of the interior spaces are consistent with the goal of distancing Chapel House from associations with traditional religious architecture. As Morgan notes, “since it was hoped that people from all religious traditions, or of none, would feel at home in Chapel House, no traditional religious architectural style could be used in the building; the religious symbols would be provided by the works of art in the house” [15].

Responsibility for selecting these “religious symbols” fell to Morgan, who selected and purchased many Asian artworks during his travels to South, Southeast, and East Asian countries, supported by Colgate’s Fund for the Study of the Great Religions of the World. Some works were commissioned for Chapel House, notably Elbert Weinberg’s dramatic bronze bas-relief “Revelation,” installed over the library fireplace; other works were anonymous donations. Morgan’s criteria for inclusion are stated in the introduction to an early edition of the collection guide:

In selecting the works of art for Chapel House, the aim has been to provide objects of artistic merit, from as many religious traditions as possible, through which the artist sought to express religious insights worthy of careful study by anyone who is seeking a better understanding of the religious dimensions of life. No work of art wins a permanent place in Chapel House until we have lived with it for several months and have found that as we get to know it better it continues to reveal more deeply those religious dimensions. If better works of religious art become available, these will be replaced…. This is not a museum of religious art. Each work merits careful and repeated study in order to begin to grasp the insight reflected in its creation [16].

Figure 3: View of library as seen from entrance; large crucifix is by Ivan Meštrović; Zen landscape painting by Usho Kaihoku is installed on right next to the window (photo by Kevin Trainor)

Figure 4: View of library with SOM-designed chairs facing fireplace (photo by Kevin Trainor)

Figure 5: View of Elbert Weinberg’s sculpture, “Revelation” (photo by Kevin Trainor)

Entries in the guide include historical and cultural background information, as well as efforts to suggest an object’s religious significance and, in some cases, guidance on how one should view it. For example, the entry for a Japanese landscape painting in the library observes:

This is a Zen landscape painting by Usho Kaihoku (1533-1615), some of whose paintings are national treasures in Japan. The two small figures on the path suggest a proper perspective for human beings in the natural world. One might view this perspective from the blue chair, but perhaps the insight communicated is best discerned from the floor. This old sumi-e … painting does not shout its message but speaks softly to those who take the time to get to know it [17].

Figure 6: Zen landscape painting by Usho Kaihoku (photo by Kevin Trainor)

As this entry suggests, Chapel House’s lack of any explicit program of religious practice or regular schedule of instruction by authoritative teachers (apart from those represented in the books in the library) should not be equated with the absence of any formalized program of religious discipline. Morgan’s role in conceiving and materializing the distinctive interior spaces and their contents reflected his understanding of what the “great religions of the world” could provide to those prepared to undertake their own experiments within Chapel House’s religious laboratory. The guide, copies of which are found throughout the complex including all the guest rooms, could be seen as a kind of operating manual for how one should ideally be shaped by the thoughtfully curated collection of religiously inspired objects, supported by the regimen of solitude and silence expected of residential guests [18].

Figure 7: Cover of current Chapel House guide (photo by Kevin Trainor)

It is significant that the Chapel House complex was initially called the “Meditation Center” at Colgate University, but was renamed “Chapel House” before its opening [19]. The new name reflects its two basic structural components: a rectangular “chapel” for prayer and meditation and a rectangular “house” which, includes, on the entrance level, the library, director’s office, music room, dining area, kitchen, and resident supervisor’s apartment and, on the lower level, houses a set of five rooms for overnight retreatants, each with adjoining bathroom [20]. These two structures, situated perpendicular to each other, are connected by a glassed-in corridor the provides the main entrance to the complex, where visitors enter and turn either left to visit the chapel, which never closes, or right to enter the house, which has more limited hours.

This change in the center’s name points to one of the central tensions in its history and in the distinctive habitus that it embodies for those who visit it. If the interior space of the house is designed to provide an environment deeply saturated with powerful religious symbols from a variety of religious traditions, the chapel could be said to provide a space deliberately emptied of such external stimuli to facilitate inwardly focused contemplative practices. The chapel is nearly devoid of religious symbols except for a large wooden cross; this cross was originally suspended from the glimmering glass mosaic reredos at the end of the chapel, and now is stored out of sight behind it [21].

Figure 8: View of chapel with cross hidden from view behind reredos and altar railing removed (photo by Kevin Trainor); chapel with cross and altar railing can be viewed at https://www.facebook.com/ColgateChapelHouse/photos/a.1510304269294256/1510304272627589/

The rationale behind the initial inclusion of the cross and its subsequent removal sheds light on some key tensions in the religious ideals and practices that have shaped the history of Chapel House, which the three directors have sought to negotiate in their efforts to create and maintain a religious space that simultaneously instantiates and affirms the value of a diversity of religious traditions and practices while also seeking to avoid privileging one religious tradition over another [22]. As noted earlier, Chapel House’s founding donor self-identified as a Christian, and she requested that the chapel include a cross; this request is reflected in the architectural plans for the chapel that SOM provided, which also incorporated a slightly elevated platform with a removable altar railing in front of the mosaic reredos and mounted cross [23]. Morgan provides the following rationale for the inclusion of the cross in this early version of the guide:

The presence of the cross in the chapel is an acknowledgment that the person who provided the endowment for Chapel House saw her act as a Christian act and that the chapel was built by Christians. The presence of the cross also indicates the importance of religious symbols in prayerful and meditational reflection, but, at Chapel House, not of their requirement. If one prefers a different symbol, others may be used either with the presence of the cross or singularly with the floor to ceiling curtain drawn. If one prefers to use no symbol at all the curtain may be drawn and the space used according to one's preference [24].

In another account of the chapel written for a visit by his sons, Morgan notes: “Over the years the curtain has rarely been pulled, Hindu and Buddhist visitors said they like the cross as a symbol of a place of worship, and they often have their own images with them” [25]. But there is also evidence that Morgan harbored reservations about this arrangement. In an account of Chapel House that he wrote in 2003, he noted in a parenthetical comment: “My preference would have been only a removable cross that could be placed on the altar, with no religious symbol permanently in the chapel” [26].

The cross remained in the chapel during John Ross Carter’s nearly four decades as director, a time marked by relatively few changes in the center apart from some necessary repairs and an updating of the collections. The directorship of Steven Kepnes, beginning in 2013, has brought significant change, commencing with a major renovation that necessitated the complete closure of the center and the deinstallation and storage of all the artwork. The primary goal of the renovation was the installation of an elevator and the reconfiguration of several interior spaces to make them ADA accessible, along with significantly increasing the building’s energy efficiency. Accessibility concerns also led to a subdivision of the resident supervisor’s apartment to create space for relocating the music room, freeing up space for a new, more accessible, dining room [27].

The deinstallation of all the art and artifacts, most of which had remained fixed in place since their acquisition and installation during Morgan’s directorship, created an opportunity to reassess and reconfigure the collections. One of the current director’s innovations was the creation of a Chapel House advisory board comprised of university faculty and administrators, and this group has played an important role in shaping significant changes during the past decade, including the recent decision to remove the cross from the front of the chapel and put it in storage behind the reredos. With significant effort, the cross can be temporarily reinstalled if requested, but this has happened rarely [28]. In place of the old curtain that could be drawn in front of the cross is now a large retractable screen, kept retracted when not in use, paired with a ceiling-mounted digital projector and speakers at the rear of the chapel, easily connected to a laptop computer for presentations [29].

Figure 9: Cross with mounting bolts suspended on wall behind reredos (photo by Kevin Trainor)

The significance and appropriateness of the cross’s presence in the chapel has, not surprisingly, elicited a variety of opinions over the years, though it is noteworthy that the advisory board unanimously agreed to have it moved out of sight [30]. For my purposes here, it illuminates a fundamental tension between the idea of a generic “religious” symbol (implied in Morgan’s observation above that the cross communicates the “importance of religious symbols” in religious practice) and the sorts of complex social negotiations that shape a particular symbol’s meaning and efficacy, including its possibility of being seen at all.

This is further illustrated by two other important changes in the Chapel House collections under the leadership of the current director: an effort to categorize and position objects by the religious traditions that they represent and the addition of objects representative of African and Native American religious traditions. In Morgan’s guide, objects are organized according to their physical location in the building, and each object seems to be regarded as unique and directly present to the gaze of the viewer, as informed by the object’s description in the guide. In the new guide, each object is presented as representative of a particular religious tradition, with, for example, all “Buddhist” objects grouped together [31]. This is made explicit in the introduction to the artwork in the current guide:

In the following pages the works are grouped by religious tradition largely for the convenience of taxonomy. The works themselves vary greatly as these living traditions have moved through time and place. Local syncretism, different sects, and individual vision are all at work in the creation of any single piece. In Chapel House one will find that no single room is completely given to any single religion.

Thus the works find conversation with each other, providing the viewer an opportunity to contemplate how these various traditions give answers to the questions of the human condition [32].

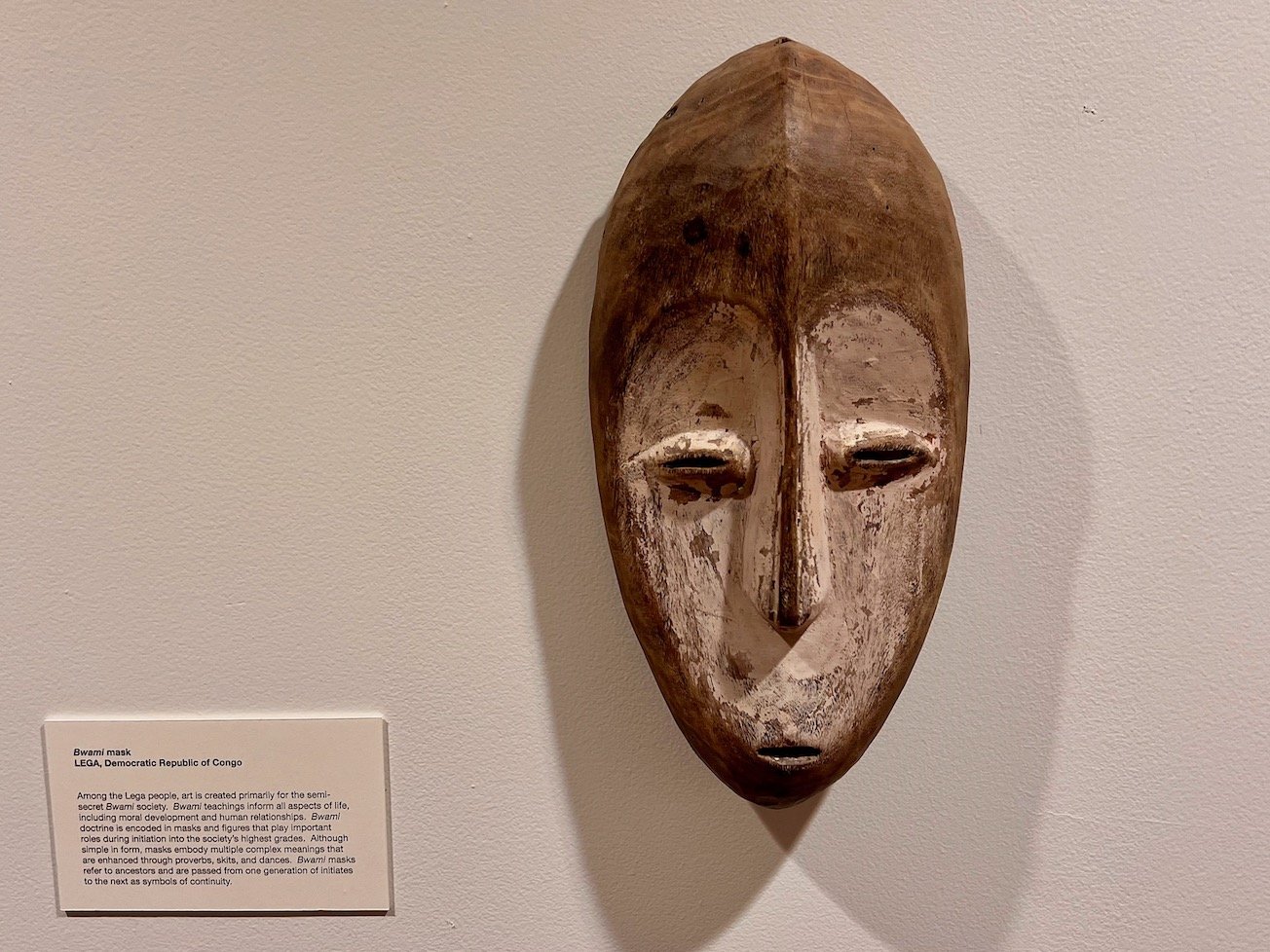

Figure 10: Lega mask from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (photo by Kevin Trainor)

This approach serves both to reinforce the idea of integrated and coherent religious traditions that address universal human questions and to illuminate the instability of these reified traditions when viewed historically and within localized social contexts. The inclusion of objects from African and Native American communities [33] further destabilizes the hegemony of the nineteenth-century notion of the great world religions, which typically positioned Christianity at the top of a graded hierarchy, and classified some societies, including African and Native American communities, as devoid of religion and thus in need of Christian missions. The rhetoric of the “great religions” clearly informed the anonymous donor’s decision to create Colgate’s Fund for the Study of the Great Religions of the World [34], and this classification is reflected in the choice of objects added to Chapel House’s collections. When grouped together by religion, objects representative of Buddhist traditions strongly dominated the collection, with roughly half of the eighty objects on display associated with Buddhism. This fact is acknowledged in the current guide:

The religious works of art in Chapel House have been collected and donated in a somewhat unsystematic manner since the building of the house without any pretension to cover all World Religions. The first director, Ken Morgan, was particularly interested in collecting Buddhist and some Hindu pieces. Christian, Jewish, and Islamic pieces were then added over time. More recently Chapel House has focused on collecting African and Native American art, especially from our local geographic area [35].

This intentional involvement of local Native American artists constitutes a further decentering of the “world religions” typology and an acknowledgement of the history of European domination of local indigenous communities. This is made explicit in the current guide’s introduction to the Native American objects in the collection:

The indigenous peoples of North America perceived themselves as living in a cosmos pervaded by powerful, mysterious, spiritual beings and forces that underlay and supported human life. Rather than a single “religion,” there were varieties of individual, tribal and regional patterns of belief and expression. Yet, there was a common regard for these spirits as ultimate sources of existence.

The European invasion of America brought about wide-ranging and long-lasting changes in Native American religious life. Christian missionary activity, alongside European diseases, ecological devastation, demographic displacement and political domination, undermined native religious complexes in many cultural crises. Christian missionaries persuaded many Native Americans to reorient themselves to Christian cosmology and ritual. Thus Native American religions today often display a mixture of indigenous and Christian motifs [36].

The salience of this historical framing, as well as the problematic nature of the category of “religion/s” for adequately representing the lived religion of Native Americans, is illuminated by the presentation of the only other object in the collection created by a Native American artist, a “Native American Cross,” classified in the guide as a Christian artwork. The guide notes the long history of native beadwork, and its use beginning in the nineteenth century for creating objects to sell at tourist destinations. It concludes:

This cross, a plaque with beads on velvet, was created by Sheila Escobar from the Mohawk Nation, Turtle Clan, in honor of her husband’s Auntie. It won a First Place award at the Indian Village at the New York State Fair for its artistry. After learning to make rosettes from her Onondoga grandmother and traveling with her to trade shows, Sheila was inspired to continue learning how to create this beadwork and preserve her indigenous heritage [37].

This artwork, and its connections to the history of regional indigenous communities, opens up a messier and more dissonant story of religiously inflected social interactions, including forms of violence and injustice, and the complexities of religious identity.

Figure 11: Beaded cross created by Sheila Escobar, member of the Mohawk Nation (photo by Kevin Trainor)

Another significant development under the current director’s leadership are new forms of outreach, which include the addition of a staff person responsible for running programs specifically directed toward bringing more Colgate students to Chapel House. When students and other new visitors first enter the center, this staff person now provides a formal orientation to the artwork at Chapel House [38], a departure from the earlier practice of allowing each visitor to discover the collections on their own. Apart from raising student awareness of what the center offers, these formal orientations provide another means, beyond the guide, through which particular objects in the collection are highlighted and interpreted [39], including how visitors should engage with them. When I was led through this orientation, attention was quickly drawn to “Silence,” a bronze sculpture in the lobby by Alfeo Faggi, which Morgan acquired for Chapel House in 1966. It was explained that the statue exemplifies the importance of maintaining silence while in the center, as well as the fact Chapel House is not an art museum and consequently the objects in the collection should be engaged with physically. To bring this message home, I was told the story (also included in the guide) of how not long after the sculpture was received, Morgan returned it to the artist because he felt it lacked a protective coating. The artist responded that the sculpture was meant to be touched and assured the director that its patina would develop after about fifty years of handling. Yet clearly there are circumstances when physical contact is discouraged. This became clear when we visited the music room and attention was directed to an antique prayer rug from Turkmenistan on the floor, oriented toward Mecca, which visitors are warned not to step on, but which Muslims are presumably welcome to use when praying.

Figure 12: “Silence” sculpture by Alfeo Faggi located in entrance foyer (photo by Kevin Trainor)

Figure 13: View of music room with prayer rug on floor oriented toward Mecca (photo by Kevin Trainor)

Several observations can be made about these new forms of outreach to students. In one sense they clearly reflect and expand upon the continuing legacy of Chapel House as a center for the study and practice of religion. This was enabled by the original donor’s funding of Kenneth Morgan’s career-long commitment to supporting the education of scholars and students about religious traditions other than those that have traditionally dominated the religious studies curricula of American universities [40]. This approach to learning was grounded in a conviction that understanding requires a personal engagement with the religious practitioners of those traditions, and Morgan, supported by the Fund for the Study of the Great Religions of the World, cultivated an extensive network of relationships between American scholars of religion and influential practitioners of religious traditions around the world, many of whom were brought to campus for a time and housed in Chapel House. John Ross Carter, a scholar of Buddhist traditions, continued and enriched this legacy during his nearly forty years as director.

Underlying the creation of Chapel House was the conviction that developing an understanding of religious traditions other than one’s own requires more than the effective transmission of objective information about world religions in a classroom setting [41]. As facilitated by the building’s design and the regimens of practice that it encourages (including a silencing of input from the campus and world at large), visitors to Chapel House are shown how to immerse themselves in the collections of books, artworks, artifacts, and music with an appropriate attitude of respect and sympathetic engagement, ideally supported by undertaking some form of contemplative practice for which the chapel was designed. At the same time, the ethos of Chapel House remains deeply reflective of a Protestant Christian privileging of individual experience and forms of interiority distant from the collective practices of religious communities and the frequently divisive dynamics of lived religion. During the past decade, however, the current director and his advisory board have repositioned the Chapel House collections in ways that make possible a wider diversity of perspectives on religion and effective forms of engagement for those who visit.

Acknowledgements

Several individuals provided support for this research. My thanks go to Steven Kepnes, Rodney Agnant, Kathy Keyes, Carol Ann Lorenz, Christopher Vecsey, Nicholas Adams, Anne Clark, and the staff of Colgate University Archives.

Notes

[1] This donor also provided funding, through Morgan’s mediation, for establishing the Center for the Study of World Religions at the Harvard University Divinity School.

[2] Moscow’s Central Anti-Religious Museum is a notable exception to this general pattern.

[3] Morgan, who completed all the requirements except the thesis for his Harvard doctoral degree, was initially hired as Colgate’s chaplain in 1946. The salary for his faculty appointment and directorship of Chapel House was subsequently covered directly by the Fund for the Study of the Great Religions of the World, established in 1957. This funding arrangement afforded him and Chapel House an unusual degree of autonomy from university oversight.

[4] Undated brochure, Colgate University Archives; the center’s current website states: “Chapel House is a place for people of all faiths seeking deeper religious insight and by those who acknowledge no religious faith”; see https://www.colgate.edu/about/campus-facilities/chapel-house.

[5] The major exception is the weekly Quaker meeting, which began gathering in the chapel when it opened in 1959; the meeting moved elsewhere in the 1980s but returned in 2015. Morgan was a member of this community. In its early years, a few other communities met regularly in the chapel, including Jewish students and Christian Scientists. In more recent years, a weekly schedule of Mindfulness sessions aimed at Colgate students has been instituted (see below for more on programmatic efforts to bring Colgate students to Chapel House under the center’s current director).

[6] Kenneth Morgan, “Chapel House at Colgate University,” no date, Colgate University Archives.

[7] This experience is discussed in detail in Morgan’s unpublished memoir, “Memories,” completed in 2007. My thanks to Alan Morgan for sharing his father’s memoir with me.

[8] Original Deed of Gift, 1958, as cited on the center’s website: https://www.colgate.edu/about/campus-facilities/chapel-house/vision-statement. In this article I observe the center’s commitment to maintaining the anonymity of the original donor, whose identity and background are discussed in Nicholas Adams, “’You Young Men Are So Sure’: Architectural Ethos at J. Walter Severinghaus’ Chapel House,” SOM Journal 10 (2017): 9-23.

[9] Morgan, “Memories,” 278.

[10] Morgan, “Chapel House at Colgate University.” SOM was an innovator in producing integrated office spaces that incorporated contemporary artwork. There is no record of which SOM designers, other than Severinghaus, contributed to the project, but Nicholas Adams has suggested in a private communication that Joanna Diman, who provided landscape design for many SOM projects during this time, may have been involved. Diman’s work is profiled in Nicholas Adams, “Joanna C. Diman (1901–91): A ‘Cantankerous’ Landscape Architect at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 77 (2018): 339-48. My thanks to the author for sharing this article.

[11] Morgan, “Memories,” 268.

[12] Adams, “’You Young Men Are So Sure,’” 16. For the history of SOM, see Nicholas Adams, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill: SOM since 1936 (Milan: Electra Architecture, 2007).

[13] On Saarinen’s MIT Chapel, see Joseph M. Siry, “Tradition and Transcendence: Eero Saarinen’s MIT Chapel and the Nondenominational Ideal” in Modernism and American Mid-20th Century Sacred Architecture, ed. by Anat Geva, 275-95 (New York: Routledge, 2019). Another notable contemporary Modernist non-denominational chapel is Mies van der Rohe’s chapel on the IIT campus; see Ross Anderson, “Minimal Ritual: Mies van der Rohe’s Chapel of St. Savior, 1952” in Modernism and American Mid-20th Century Sacred Architecture, 15-30.

[14] Adams, “’You Young Men Are So Sure,’” 18.

[15] Morgan, “Chapel House at Colgate University.”

[16] “An Introduction to the Works of Art in Chapel House,” no date, p. 12f., Chapel House Archives.

[17] “An Introduction to the Works of Art in Chapel House,” 12f. The current edition of the guide, dating from 2021, lacks this instruction about where to sit in viewing this painting and its religious message.

[18] Residential guests are required to spend a minimum of two nights in residence, to refrain from the use of drugs and from walking down to the Colgate campus, and are expected to maintain silence except at the communal meals. While Chapel House now provides Wi-Fi access through Colgate’s guest network, a printed notice in each guestroom informs residents that they are expected to avoid using telephones and to refrain from web browsing and computer use in the library.

[19] Morgan explains that confusion about the meaning of the word “meditation” led them to change the name to Chapel House (“because it is simply a chapel and a house”) to avoid “preconceptions” about what happens there (Morgan, “Chapel House at Colgate University”). Morgan’s understanding of meditation practices is explored in his Reaching for the Moon: On Asian Religious Paths (Chambersburg, PA: Anima Publications, 1990).

[20] Chapel House originally had seven guest rooms, one of which was later converted to an emergency exit. A significant renovation begun in 2013, aimed in part at making the center more ADA accessible, further reduced the number of guest rooms from six to five. Planning for the 2013 renovation began while John Ross Carter was the director.

[21] Also stored behind the reredos is a wooden arc and torah scroll kept out of sight that can be brought out for Jewish services. And in one of the two private, velvet-curtained “oratories” there is a kneeler positioned before an altar surmounted by a standing crucifix that belonged to the chief donor. Prior to the renovation, this crucifix was displayed in the music room.

[22] Kenneth Morgan was director from 1959-74, John Ross Carter from 1974-2013, and Steven Kepnes from 2013 to the present, all professors of Religion at Colgate.

[23] The gently peaked roof, gold-tinted glass walls, and simple wooden cross for me evoke a non-denominational Protestant worship space, while the golden reredos behind the cross is more reminiscent of Byzantine ornamentation. Compared, for example, to the interior of Saarinen’s MIT chapel, Chapel House feels distinctly Christian, even in its current form with the cross hidden from view behind the reredos.

[24] “An Introduction to the Works of Art in Chapel House,” 43.

[25] Kenneth Morgan, “Chapel House at Colgate University since 1959,” no date, Colgate University Archives, 3.

[26] Kenneth Morgan, “Chapel House at Colgate University in 2003,” undated text in Colgate University Archives, 1.

[27] The original configuration included a separate dining room next to the music room; when I first visited Chapel House in the early 1970s, this dining area had been incorporated into the resident supervisor’s apartment and the new dining area shifted to the long corridor adjoining the kitchen where it remained until the 2013 renovation.

[28] This option is stated on the Chapel House website: “Because the space is intended for use by those of any religious background—or none—the Christian cross usually sits behind the reredos. Upon request the Christian cross can be placed on the reredos for specific meetings, prayers and events. This provides the space with the flexibility to serve all visitors, regardless of their religious affiliation”; see: https://www.colgate.edu/about/campus-facilities/chapel-house.

[29] During the pandemic, small groups of students isolated in their rooms were invited to come to the chapel and sit while the projector displayed images and music for meditation. My thanks to Kathy Keyes for sharing this information with me.

[30] Private communication with Steven Kepnes.

[31] The guide ends with a listing of objects by room, each keyed to the page on which that object is discussed. Some objects are now grouped together by tradition in the music room.

[32] “An Introduction to Chapel House and Its Works of Art,” unpublished guide in Chapel House archives, updated 1/26/2021, 7.

[33] Kepnes drew upon the expertise of two Colgate faculty colleagues, Carol Ann Lorenz and Christopher Vecsey, in acquiring these objects. While two masks from Nigeria have been mounted at the top of the stairs leading down to the lower level, most of the African and Native American objects are installed on the lower level where the guest rooms are located, an area that casual visitors are less likely to see. One of the Native American artworks, depicting a creation story, is comprised of a series of twelve pen-and-ink drawings that fit the continuous wall space available on the lower level. A new work by Mohawk artist Roger Parish will soon be added to the collection.

[34] “Great” has now been dropped from the Fund’s name.

[35] “An Introduction to Chapel House and Its Works of Art,” 7.

[36] “An Introduction to Chapel House and Its Works of Art,” 7.

[37] “An Introduction to Chapel House and Its Works of Art,” 7. This information is also included on the label next to the cross.

[38] When I visited Chapel House last year, this Assistant Director of Programming position was held by Rodney Agnant, who led me through his customary orientation. His outreach to students and interested guests also included leading a regular schedule of weekday morning Mindfulness meditation sessions. This position is currently vacant, and it remains to be seen if regular Mindfulness sessions will again be offered.

[39] The recent addition of African and Native American objects was highlighted in this orientation.

[40] Over the course of ten years, the fund supported fellowships for more than fifty scholars who taught religion at undergraduate institutions to spend a year intensively studying Asian religions, including at least four months residing in Asia. This is detailed in Kenneth Morgan, “Annual Report, 1968-69,” May 30, 1969, Colgate University Archives.

[41] Several objects from the Chapel House collections are currently on extended display for instructional purposes in a campus classroom.

Selected references

Adams, Nicholas. “Joanna C. Diman (1901–91): A ‘Cantankerous’ Landscape Architect at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 77 (2018): 339-48.

_____________. “‘You Young Men Are So Sure’: Architectural Ethos at J. Walter Severinghaus’ Chapel House.” SOM Journal 10 (2017): 9-23.

Anderson, Ross. “Minimal Ritual: Mies van der Rohe’s Chapel of St. Savior, 1952.” In Modernism and American Mid-20th Century Sacred Architecture, edited by Anat Geva, 15-30. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Morgan, Kenneth W. Reaching for the Moon: On Asian Religious Paths. Chambersburg, PA: Anima Publications, 1990.

Siry, Joseph M. “Tradition and Transcendence: Eero Saarinen’s MIT Chapel and the Nondenominational Ideal” in Modernism and American Mid-20th Century Sacred Architecture, edited by Anat Geva, 275-95. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Kevin Trainor is Professor of Religion Emeritus at the University of Vermont. His research centers on Buddhist traditions in India and Sri Lanka, with particular attention to Buddhist material culture, relic practices, and pilgrimage. He is co-editor, with Paula Arai, of the recently published Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Practice (2022). He completed his undergraduate degree at Colgate University in 1974, where he studied with Kenneth Morgan and John Ross Carter, and first encountered Chapel House.