Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai, Egypt

By Ryan Abramowitz, Elizabeth Elliott, and Alice Isabella Sullivan

History

The Sinai Peninsula occupies Egypt’s westernmost reach of the Mediterranean, bordered by this sea to the north and the Dead Sea to the south, the Suez Gulf to the west, and the Aqaba Gulf and Israel to the east. The jagged landmass has long been of interest to Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities. It is, for example, the place where God made himself known to the Old Testament prophet Moses in the biblical narrative of the Burning Bush (Exodus 3). It was here, too, that the Yahweh god delivered to Moses the Ten Commandments upon leading the Jewish people out of Egyptian servitude and into the desert (Exodus 20:2–17). Muslims also revere this place as the site in which the prophet Muhammad granted the Christian community living there a signed article of immunity from some Islamic laws (notably those pertaining to iconophilia) after they received him hospitably (Ramljak 1987, 2). In addition to the biblical and Qur’anic importance ascribed to Sinai, Egyptian communities have identified this place as holy. Preserved rock-cut statues point to a kind of votive based moon-worship by Egyptians from at least the First Dynasty (3100 BCE) (Eckenstein 1980, 12). That independent groups have intuited Sinai to be a locus sanctus, a place in which the powers of heaven are more easily tapped on earth, is noteworthy.

Figure 1. Satellite map of the Sinai Peninsula with modern place names. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-19267223

The Sinai Peninsula hosts the holy Mount Sinai, known locally as the Gebel Musa. Beginning in the 3rd century CE, Christians settled there in order to be close to biblical sites and to distance themselves from Roman religious persecutions (Archbishop Damianos 2004, 335). Ascetic life at the time materialized as a loose collection of hermit cells cut into and around the mountain (Chryssavgis 2004, 2). Over time, as more ascetics ventured into the Sinai wilderness to live at the base of that mountain whose rocks shone to a fiery degree, the hermits began to congregate weekly to worship (Eckenstein 1980, 99). Asceticism, therefore, started to take on a distinctly monastic flavor of worship as the hermits increasingly and intentionally sought out communal times for prayer as opposed to a strictly isolated form of worship. The shift toward a more congregational lifestyle may have also been a practical, life-preserving decision, being that the hermits not only engaged with, but were a part of, the larger picture of a “restless movement of peoples along the eastern marches of the later Roman Empire,” which at times brought along episodes of violence (Forsyth 1968, 4).

Emperor Constantine’s 313 CE Edict of Milan legalized the practice of Christianity across the Roman Empire, which gave rise to further alterations to the style and setting of worship at Sinai. The general rise in pilgrims visiting holy sites did not exclude this place. Ascetics living at Sinai, despite having ventured into the desert to live a more solitary life, appear to have been receptive to those who made the journey. When the Spanish nun Egeria departed from Sinai, she praised the monks for their hospitality, saying: “I cannot sufficiently give thanks for all those holy ones who were gracious enough to receive my unimportance in their monastic cells with a willing mind or to lead me surely through all the places that I was always searching for according to the holy scriptures” (McGowan and Bradshaw 2018, 114). Egeria concludes her passage on Sinai by relating that several of the monks even escorted her to her next destination, Pharan.

In conjunction with the added presence of religiously motivated travelers was the construction of monastic infrastructure. According to tradition, Saint Helena (c. 246–330 CE), the mother of Emperor Constantine, commissioned a small church and tower, which may have been dedicated to the Theotokos (Mother of God), to be constructed near the site of the Burning Bush. These structures were intended to assist the ascetics in their defensive and religious endeavors (Eckenstein 1980, 99; Evans 2004, 12; Nardi 2011, 29, 31).

Figure 2. General view of the Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai, Egypt. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Saint-Catherines-Monastery

The monastery’s current appearance, however, is the result of building projects from the time of Justinian I (r. 527–565). At the request of the monks living there, the church, according to inscriptions carved into the ceiling beams, was built in the years between the deaths of Empress Theodora and Emperor Justinian (c. 548–565 CE) by a local architect whose name survives: Stephonos of Aila (Eckenstein 1980, 129; Evans 2004, 16). The monastery’s fortifications were constructed also at this time, and were accompanied by 200 soldiers the emperor had stationed there. The bulwarks served a range of functions: they enclosed and distinguished the monastic community from the outside world; protected the monks from raiders, acting as a military watchpost so that the army might keep track of enemy movements in the region, especially into Palestine; and was just one piece of a greater network of defensive stations whose broad reach covered the territory between Armenia and Egypt (Forsyth 1968, 4). For a walled-monastery with intended defensive functions, the decision to occupy the area at the foot of Mount Sinai as opposed to higher ground is a curious and debated one.

Despite this, the fortifications, which were set up at the request of the monks living there, granted the Christian community certain privileges (Evans 2004, 13). The defensive walls seem to have served their purpose, preserving not only the community but the church and much of the monastery’s original structures, making the place the oldest functioning Orthodox Christian monastery in the world. The campus as it stood in the 6th century enclosed within its walls the tower donated by Saint Helena, a bakery, guesthouse, stable, garden, cells for the monks, monastic buildings, and of course a church (Eckenstein 1980, 128–129). The monastery has predominantly retained its original appearance with the exception of several newer edifices, which include the 19th-century Russian belfry and the conversion of the original guesthouse into a mosque (Forsyth 1968, 7).

Saint Catherine’s, as it is now called, also boasts an impressive collection of manuscripts, hundreds of sumptuous liturgical objects, and even greater numbers of icons (over 2,000). The monastery was meant to be a site to receive precious things as an imperial dedication, and this practice only intensified over time. The significance of the en masse survival of icons, liturgical objects, and manuscripts, to which we return in greater detail below, is unquestionable and is a testament not only to the militaristic tactics undertaken to safeguard the monastery but to the diplomatic ones as well (e.g. the Prophet Muhammad’s previously mentioned decree, and a forgery of a decree said to be by Justinian that issued the monastery autonomous rule, which was accepted despite its dubious origins).

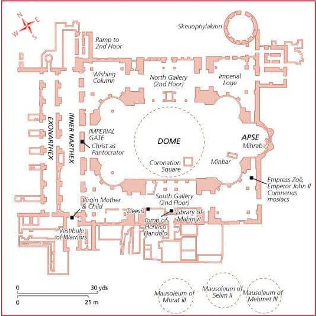

The preservation of the Church of Saint Catherine (a.k.a. Church of the Transfiguration, originally known as the Church of the Theotokos) is also exceptional, being just one of several 6th century churches that survive nearly unchanged and unlike other imperial churches. If Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (now Istanbul) stands as the paragon of early imperial Byzantine church architecture, Saint Catherine’s is indubitably dissimilar in form and function from its contemporary despite having the same patron, Emperor Justinian. Both churches combine in new ways the traditional basilican and central plans of early Christian churches. Whereas the longitudinal arrangement of Hagia Sophia places emphasis on the monumental central dome, Saint Catherine’s presents an aisled church that culminates in a liturgical space that adapts the traditional Byzantine cross-in-square church layout.

Figure 3. Annotated Plan of Hagia Sophia. https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/ayasofya

Figure 4. Plan of the Church of Saint Catherine. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Sinai-Monastery-of-St-Catherine-katholikon-ground-plan-after-Forsyth-The-monastery_fig1_351519815

The plan of Saint Catherine’s is composed of a narthex, central nave, two side aisles, and an apse at the eastern end. The U-shaped path of circumambulation is interrupted by entrances to various side-chapels that line the northern and southern sides of the church. Both the side chapels and the sanctuary were adorned with numerous icons. Rather than drawing from the artistic milieu of the imperial city of Constantinople, it appears that Stephonos adapted the architectural dialect of Syro-Palestine while designing Saint Catherine’s. The church is, indeed, similar to other pilgrimage churches that were constructed at this time in Syro-Palestine and Cilicia, particularly the Holy Sepulchre and Martyrium in Jerusalem and Qalat Seman in Syria at Deir Semaan (Forsyth 1968, 17). What makes Sinai unique from such comparable sites is that the church was designed not just to house the cult object (i.e. the Burning Bush or Saint Symeon’s column) but the monks themselves (Forsyth 1968, 16). Procopios of Caesarea, Justinian’s court historian, emphasizes this fact, telling us that Justinian built “them”—the monks of Sinai—a church “ἐκκλησίαν ᾠκοδομήσατο” (Procopius and Dewing, 356–357).

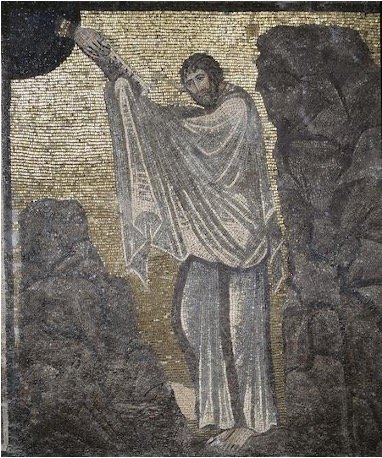

One element that Saint Catherine’s and Hagia Sophia share is the use of mosaics, the Byzantine medium par excellence, to adorn the upper levels of the interiors. Since Saint Catherine’s has not suffered the same iconoclastic fate as Hagia Sophia during the 8th and 9th centuries, however, the 6th century mosaics were preserved at Sinai. Although left in a precarious state due to the passing of centuries and earthquakes, the mosaics, which were almost entirely removed from the mortar of the wall in certain places, were preserved in 1847, and again in 1959, and more recently carefully restored in 2010 (Nardi 2011). Set against a background of lively, luminescent gold tesserae, the New Testament scene of the Transfiguration—when the nature of Christ was made clear to Saints Peter, James, and John at the summit of Mount Hebron (Matthew 17)—shines down upon the altar. The mosaics are a key visual here as the nave is separated from the altar by an iconostasis (or icon-adorned gate), which prevents monks and pilgrims from seeing the miracle of the Eucharist, the transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, unfolding at the main altar during liturgical celebrations.

Although the major sightlines to the altar have been blocked by the iconostasis, the mosaics adorning the semi-dome just above it marked the space below as sacred (Elsner 2016). Old and New Testament prophets and saints are woven into a singular scene that not only verify the authenticity of Christ’s claim to be the Son of God but also overlays the sacrality of the event on the holy Mount Hebron with that of the holy Mount Sinai. This is further demonstrated by the placement of the scene where Moses removed his sandals before the Burning Bush, and the scene in which he received the Ten Commandments, in the corners of the wall surmounting the semi-dome. Although Christ himself did not visit Mount Sinai, a continuity is drawn between Moses and the former: Moses is present in both scenes. The light that emanates from the body of Christ, moreover, points both to the New and Old Testament characters, making the interconnectedness of all the figures even more poignant.

Figure 5. Apse mosaics of Church of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. https://iconreader.wordpress.com/2011/08/06/transfiguration-icon-the-event-and-the-process/stcathsinaiapsehq/

Figure 6. Detail of the semi-dome mosaic in apse of Church of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. https://www.europeanheritageawards.eu/winners/collaborative-conservation-apse-mosaic-transfiguration-basilica-st-catherines-monastery/

Figure 7. Moses Removing his Sandals Before the Burning Bush. https://www.akg-images.com/archive/-2UMEBM216FPI.html

Figure 8. Moses Receiving the Ten Commandments (Law). https://fortnightlyreview.co.uk/2014/07/mango-sinai-mosaic/

Collections

The monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai is home to impressive holdings of religious objects and texts dating to the 4th century. The dry climate, longevity of the monastery, and the extreme isolation has meant that the collection has remained relatively safe from destructive forces. With objects and texts that can be traced from Europe to the Middle East, the collection of icons, manuscripts, documents, and liturgical objects, demonstrates the spiritual and physical reach and influence of Saint Catherine’s.

Icons

Most notably, the collection of the monastery traces the history of the icon from Late Antiquity until the modern era, including icons that pre-date the Iconoclastic period in Byzantium, during which the function of images in Christian worship was intensely debated. This controversy had wide religious, social, and political implications. The two key periods of Iconoclasm lasted from 726 to 787 and from 814 to 843. During this time, figural religious images were routinely destroyed. Icons were burned, and image cycles in churches were removed and replaced with Christian symbols, like the cross. The Church of Hagia Irene (now Istanbul), for example, retains the large cross set up in the apse during the first Iconoclastic era.

Few examples of icons survive from the pre-Iconoclastic period in the Eastern Christian cultural sphere. Most notable among them are the following Sinai icons:

An icon of Christ Pantokrator

An icon of the Virgin with Child among saints and angels

An icon of Saint Peter

Figure 9. Icon of Christ Pantokrator. https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/catherine-pantocrator

Figure 10. Icon of the Virgin with Child among Saints and Angels https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mary_%26_Child_Icon_Sinai_6th_century.jpg

Figure 11. Icon of Saint Peter. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Peter_Icon_Sinai_7th_century.jpg

Dated to the 6th and 7th centuries, these icons were created using the encaustic painting technique on wood, with gold leaf used to accentuate certain aspects of the holy figures, like their haloes and key highlights of their garments and attributes. These examples from Sinai, moreover, share similarities in composition, technique, and details with four icons now in The Khanenko Museum in Kyiv, Ukraine, also dated to the 6th and 7th centuries:

An icon of the Virgin and Child

An icon of Saint John the Baptist with busts of Christ and the Virgin Mary in roundels at the top

An icon of Saints Sergius and Bacchus with Christ’s visage in a roundel at the center

An icon showing a male and female martyr

Figure 12. Icon of Saints Sergius and Bacchus. https://presse.louvre.fr/the-origins-of-the-sacred-image/

Figure 13. Icon of the Virgin and Child. https://presse.louvre.fr/the-origins-of-the-sacred-image/

Figure 14. Icon of Saint John the Baptist. https://presse.louvre.fr/the-origins-of-the-sacred-image/

Figure 15. Icon of Male and Female Martyr. https://presse.louvre.fr/the-origins-of-the-sacred-image/

These icons journeyed from Sinai to Kyiv in the mid-19th century under the watchful eye of Archimandrite Porphyrius Uspensky (1804–1885). This transfer could have coincided with the period in early 1865 (February 14) when Archimandrite Porphyrius was consecrated Bishop of Chigirin and appointed the first vicar of the Eparchy of Kyiv. He held this position under his former tutor from the seminary in Kostroma, Metropolitan Arseny (Moskvin). These early icons, thus, would have helped reestablish and legitimize a spiritual connection between Kyiv and Byzantium—a connection first established in the late 10th century with the conversion of Prince Volodymyr the Great (r. 980–1015) to Eastern Orthodoxy. More recently, the icons have been on display in the Louvre Museum as part of the exhibition “The Origins of the Sacred Image: Icons from the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts in Kyiv” (14 June – 6 November 2023).

The importance of Saint Catherine’s to the collective Christian world is evident through the icons, objects, and texts that remain in the monastery. In the collection of 2,000 icons, many of them were donated. With depictions of laymen and royalty, with the clothing styles from Eastern and Western Europe, these icons demonstrate the breadth of support and devotion to the monastery throughout history. Some of the highlights of the collection, including the oldest pre-iconoclasm icons, are on display in the monastic museum.

Library

The library at Saint Catherine’s is one of the oldest and continuous libraries in existence. Today, there are some 3,300 manuscripts in the Old Library. Similar to the collection of icons, the manuscripts also hold some of the most important examples of early Christian texts, with the oldest dating to the 4th century.

The large number of religious texts bears testament to the devotions of the inhabitants at Mount Sinai - religious men who spent their lives in search of an ascetic Christian experience filled with study and prayer. The texts present in the collection also demonstrate the reach (extent/scope) of Saint Catherine’s. These manuscripts are written primarily in Greek, with other examples written in Arabic, Syriac, Georgian, Slavonic, Polish, Hebrew, Ethiopian, Armenian, Latin, and Persian. As with the icons, the numerous languages present in the manuscripts indicate the importance of Saint Catherine’s as a center for all Christianity, not only in the sphere of Byzantium.

One of the most important manuscripts in the collection is the Codex Sinaiticus. Written in the first half of the 4th century, the Codex Sinaiticus is the earliest complete New Testament and one of the earliest and best accounts for several books from the Old Testament (Pattie 2). In addition to its age, this manuscript illustrates how religious texts function as living documents, with edits and modifications made by users over the centuries. At some point in the 19th century, the binding of the Codex Sinaiticus was split and the folios distributed to different locations (Charlesworth, 28). Today, the manuscript is spread between four institutions: the British Library, the Library of the University of Leipzig, the National Library of Russia of Saint Petersburg, and Saint Catherine’s monastery.

Other liturgical texts provide resources to chart linguistic developments, particularly of the Greek language. This is the case with codices written in uncial, the oldest script used by scribes to write the Bible. The library at Sinai has ten complete codices in these scripts and over fifty incomplete codices (Charlesworth, 28).

The monastery also houses one of the largest collections of palimpsests—manuscripts with erased layers that preserve older, unstudied texts from previous centuries. Given the remote location of Saint Catherine’s, materials for manuscripts were not always readily available. When new writing materials were needed, a text deemed less important would be scraped clean and the parchment reused. These previous layers of texts can now be viewed and studied through advances in multispectral imaging technology. In this process, multiple images are first taken at different wavelengths and then digitally combined with certain layers and characteristics enhanced. After this process, it is possible to see the traces of the original text (Toth, 179).

Accompanying the collection of religious texts, the collection includes legal and travel records, secular writings, and correspondence. These works offer insight into religious traditions and give shape to the individuals and events that informed the history of the monastery, internal activities, and the interactions with the outside world that enabled it to survive. Many of the Greek texts in the library are available for research, as are hundreds of unexamined papyri written in Syriac, Arabic, Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopic, Georgian, Latin, and Slavonic. The collection of texts at Sinai remains a rich topic of research.

Liturgical Objects

Perhaps the least studied objects in the Mount Sinai collections— the liturgical objects—reveal aspects of the religious and routine events of the monastery, as well as interactions with the broader Christian world. These objects range from liturgical vestments and objects to large furnishings, book covers, etc. Many of these objects were photographed between 1956 and 1965 during the Princeton-Michigan-Alexandria expeditions to Mount Sinai. Some of the objects were made at the monastery, while others arrived there as gifts from far reaching corners of the medieval world. These objects speak to the importance of the monastery as a spiritual center and beacon of Orthodox spirituality throughout its long history.

Figure 16. Aquamanile. Image from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/h/hart/x-1384823/16ASINAI00413?lasttype=boolean;lastview=reslist;med=1;resnum=7;size=50;start=1;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=aquamanile

Figure 17. Bread seal. Image from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/h/hart/x-1393834/16ASINAI03447?lasttype=boolean;lastview=reslist;med=1;resnum=4;size=50;start=1;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=bread+seal

Figure 18. Koran stand. Image from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/h/hart/x-1384278/16ASINAI00222?lasttype=boolean;lastview=reslist;med=1;resnum=1;size=50;start=1;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=16asinai00222

An example of a site-specific object is the Moses Cross. This cross is housed in the chapel dedicated to the Forty Martyrs of Sinai. This large cross, 104 cm tall, surmounts the iconostasis. However, when removed to be photographed by the aforementioned team in 1960, more details of the cross were revealed. The front side of the cross is completely covered in inscriptions in uncial, bearing passages from the Old Testament and dedications to individuals. On the ends of the left, center, and right arms of the cross, images depicting Moses removing his sandals, the hands of God coming down from the heavens, and Moses receiving the law are inscribed (Weitzman 285, 1963). Just as the image and importance of Moses is noted on a monumental scale with the mosaics above the apse, the importance of Moses’ interaction with the divine for all Abrahamic religions is documented in miniature on this cross. These direct references to the events that occurred on Mount Sinai highlight a theme evident in many objects at the monastery: objects that were either made at the monastery or have specific textual or visual elements connecting them to the spiritual events of the location.

Figure 19. Moses Cross. Image from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/h/hart/x-1390448/16ASINAI02310?lasttype=boolean;lastview=reslist;med=1;resnum=8;size=50;start=1;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=ic_all;q1=moses+cross

Whereas many liturgical objects in the collection were site-specific either in their production or theme, others were donated to the monastery and do not have any overt connection to Sinai. One example of this is an image from the inside lid of a wooden box. The image shows a group portrait that includes Prince Neagoe Basarab of Wallachia (r. 1512–1521), Milica Despina of Serbia, and their six children. The figures are all kneeling in prayer toward an image of the Virgin Mary and Christ Christ emerging from the heavens above. Records show that during his lifetime, Neagoe Basarab made many donations to monastic communities on Mount Athos and other Christian centers across the Mediterranean. It is not unreasonable to assume that this box contained similar donations, but in this case to Sinai, as a way to secure prayers and remembrance from among the local monastic community and ensure the monastery’s continuity in the decades after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Like this example, many others await discovery in the collections of Saint Catherine’s and in the digital archives.

Figure 20. Lid of a wooden box showing Neagoe Basarab of Wallachia and his family. Image from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor. https://mappingeasterneurope.princeton.edu/item/neagoe-basarab-of-wallachia-and-his-family.html

Expeditions

The collections of Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai have long fascinated and delighted scholars from around the world. In 1956, George H. Forsyth (Professor of Art History, University of Michigan - Ann Arbor) embarked on his first exploratory trip to the monastery. His primary interest was the architecture of the site, but he soon appreciated the vastness and importance of the collections of icons, manuscripts, liturgical objects, as well as archives of documents and letters (Forsyth and Sears, 2016). Two years later, Forsyth departed for Sinai again, but this time with a team of experts, including his main collaborator Kurt Weitzmann (Professor of Byzantine Art History, Princeton University). As much as Forsyth delighted in the architecture of the site, Weitzmann cherished the icons, and especially those dated to the Byzantine period (4th c.–15th c.). Forsyth and Weitzman, accompanied by other colleagues and experts, set out on four research expeditions to Sinai during the summers of 1958, 1960, 1963, and 1965, intending to photograph the holdings of the monastery. The main aim of the expeditions was “to document” the monastery and its collections. The letters exchanged between Forsyth and Weitzman refer to the project as “a recording mission” aimed at capturing and preserving for future study a vast body of material difficult to access, yet so important to researchers around the world.

These expeditions—known as the Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expeditions to Mount Sinai—documented the vast collections of the monastery through black and white, 35 mm color, and Ektachrome film photography, serving as the basis for the so-called Sinai Archives at the University of Michigan and Princeton University. Princeton’s archive centers on a smaller portion of the collection, primarily the colored icon photographs, manuscript pages, liturgical objects, and the mosaics, which were of most interest to Weitzmann, as a Byzantinist, during his scholarly career. Michigan’s collection, in turn, consists of most of the correspondence, drawings and research notes, as well as images of the site and its large multi-media holdings. Together, the two archives are comprehensive; separated, they offer only a glimpse into the successful mid-20th-century expeditions.

Figure 21. Photos from the Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expeditions to Mount Sinai. Images from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

Digital Efforts

Discussions about the digitization and accessibility of the photography and documents in the Sinai Archives began in 2011. By 2015, the now-well-known “Icons of Sinai” site from Princeton was launched. This site—hosted and managed solely by the Department of Art and Archaeology at Princeton—has been a tremendous resource to many scholars over the years. However, it displayed only a relatively small portion of the collection, focusing on the colored icons that Kurt Weitzmann brought to Princeton after the expeditions. Everything else was in the Michigan collection and available in full only to the local community.

Finding a way to bring the two archives together would yield a complete record of the expeditions, both visual and textual, and the digital format emerged as the best option for such a project. It also made the content accessible to all. The initial effort began in 2018 with a preliminary project to bring together in digital form the icons held in the Michigan and Princeton collections. The gathered and combined metadata and archival images sit at the foundation of this new website, which also offers more intuitive accessibility. It makes use of the IIIF standard for images (which allows zooms in/out), Omeka S as a standard platform, shareable locators for individual images, and a robust sustainability plan. In addition to encouraging the study and research of this material among students, teachers, scholars, and the wider public, this new website aims for better display and use, data details and searchability features, as well as the preservation of the site into the future so that it can continue to grow and serve as a resource.

Figure 22. Screenshot of an entry on the Sinai Digital Archive website. Image from authors.

To date, the new website features the religious icons held in the Michigan and Princeton collections, as well as the icons only present in the Michigan archive (mostly from the post-Byzantine period and into the present)—a total of 1903 works with thousands of individual image files. In addition, it features the famed mosaics of the main church, which have been of interest to students and scholars of Byzantium for generations. By the end of 2023, the website will also feature the manuscripts and liturgical objects in the Michigan and Princeton archives, as well as improved metadata for key entries, better display and search functions, and a regularly-updated bibliography and resources page. A “Teaching Resources” page is under development, which will include recorded lectures and teaching activities to use in the classroom.

Figure 23. Screenshot of the various collections on the Sinai Digital Archive website. Image from authors.

The Sinai Digital Archive was launched on December 11, 2021 at the 47th Byzantine Studies Conference (Cleveland, Ohio). Since then, many scholars have used the Sinai Digital Archive and many graduate students have worked on the platform, improving its contents and accessibility. In 2023, the Sinai Digital Archive was awarded the 2023 Digital Humanities and Multimedia Studies Prize from the Medieval Academy of America. The project has been recognized for conforming “to many of the best practices within Digital Humanities,” for displaying an accessible interface, and for maintaining a robust sustainability plan.

This collaborative digital project leverages institutional resources in order to digitize, organize, research, and make available the Sinai collections in full to everyone, and especially to those who may not be able to travel directly to Sinai. Providing this public access and sustained scholarly interest would enable continued study, research, and teaching of the remarkable history and noteworthy collections of Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai for generations to come.

Saint Catherine’s collections—actual and digital—remain an ongoing topic of study, research, and discovery. Digital efforts are making the collections more accessible worldwide, offering a model for how other monastic or religious repositories might be digitized, displayed, and preserved for remote access and for the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Paroma Chatterjee (History of Art, University of Michigan) and the editors of this project for reading an earlier version of this text and for offering thoughtful suggestions.

Select Bibliography

Sinai Digital Archive: https://sinaiarchive.org/

Archbishop Damianos. “The Icon as a Ladder of Divine Ascent in Form and Color.” In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), edited by Helen C. Evans, 335–40. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

Baddeley, Oriana, and Earleen Brunner, eds. The Monastery of Saint Catherine. Exhib. Cat. London: Foundation for Hellenic Culture; London: The Saint Catherine Foundation, 1996.

Charlesworth, James H. “The Manuscripts of St. Catherine’s Monastery.” The Biblical Archaeologist 43, no. 1 (1980): 26–34.

Chryssavgis, John. John Climacus: From the Egyptian Desert to the Sinaite Mountain. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2004.

Eckenstein, Lina. A History of Sinai. New York: AMS Press, 1980. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=iau.31858014129195&view=1up&seq=9.

Elsner, Jaś. “Encounter: The Mosaics in the Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai.” Gesta 55, no. 1 (March 2016): 1–3.

Elsner, Jaś. “The Viewer and the Vision: The Case of the Sinai Apse.” Art History 17, no. 1 (1994): 81–102.

Evans, Helen C., and Bruce White. Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai, Egypt: A Photographic Essay. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004.

Forsyth, George H. “The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Church and Fortress of Justinian.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 22 (1968): 1–19.

Forsyth, George H., and Kurt Weitzmann. The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Church and Fortress of Justinian. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Forsyth, Ilene, and Elizabeth Sears. “George H. Forsyth and the Sacred Fortress at Sinai.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 70 (2016): 117–150.

Galey, John. Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine. Introduction by George H. Forsyth and Kurt Weitzmann. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1980.

Gerstel, Sharon E. J. and Robert S. Nelson, eds. Approaching the Holy Mountain: Art and Liturgy at St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010.

Larison, Kristine Marie. “Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: Place and Space in Pilgrimage Art.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 2016.

McGowan, Anne, and Bradshaw. The Pilgrimage of Egeria: A New Translation of the Itinerarium Egeriae with Introduction and Commentary. Alcuin Club Collections 93. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press Academic, 2018.

Nardi, Roberto. The Conservation of the Mosaic of the Transfiguration: Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai. Rome: Centro di Conservatione Archaeologica, 2006.

Nardi, Roberto. “Restoration of the ‘Mosaic of the Transfiguration’ in St. Catherine Monastery on Mount Sinai.” In Solo Mosaico: Tradition, Technique, Contemporary Art, 28–37, 2011.

Nelson, Robert S., and Kristen M. Collins, eds. Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.

Paliouras, Athanasios. The Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai. Sinai: St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1985.

Pattie, T. S. “The Codex Sinaiticus.” The British Library Journal 3, no. 1 (1977): 1–6.

Piatnitsky, Yuri. Sinai, Byzantium, Russia: Orthodox Art from the Sixth to the Twentieth Century. London: Saint Catherine Foundation in association with The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, 2000.

Procopius, and H. B. (Henry Bronson) Dewing 1882–1956. trl. On Buildings. General Index. Harvard University Press, n.d. Accessed July 18, 2023.

Ramljak, Suzanne. “The Monastery of St. Catherine: Its Art and Its History are Positively Byzantine.” Michigan Today 19, no. 3 (1987): 1–3.

Rossi, Corinna. The Treasures of the Monastery of Saint Catherine. Vercelli, Italy: White Star, 2006.

Ševcenko, Ihor. “The Early Period of the Sinai Monastery in Light of its Inscriptions.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 20 (1966): 255–264.

Ševčenko, Nancy Patterson. “The Monastery of Mount Sinai and the Cult of Saint Catherine.” In Byzantium, Faith and Power (1261–1557): Perspectives on Late Byzantine Art and Culture. Edited by Sarah T. Brooks. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. 118–137.

Toth, Michael B., and Alberto Campagnolo. “Multispectral Imaging for Special Collection Materials.” In Book Conservation and Digitization: The Challenges of Dialogue and Collaboration, 179–94. York: Arc Humanities Press, 2020.

Weitzmann, Kurt. Illustrated Manuscripts at St. Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai. Collegeville: St. John’s University Press, 1973.

Weitzmann, Kurt. The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. The Icons. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Weitzmann, Kurt, and G. Galavaris. The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Illuminated Greek Manuscripts, vol. 1, From the Ninth to the Twelfth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Weitzmann, Kurt, and Ihor Ševčenko. “The Moses Cross at Sinai.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 17 (1963): 385–98.

Ryan Abramowitz is a PhD student in the Department of the History of Art at the University of Michigan - Ann Arbor. He specializes in Byzantine pilgrimage art and architecture.

Elizabeth Elliott is a recent graduate of the Department of the History of Art and Architecture of Tufts University. She received her MA in Art History and Museum Studies and is interested in Medieval Eastern European art and architecture.

Alice Isabella Sullivan, PhD is Assistant Professor of Medieval Art and Architecture and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at Tufts University. She is co-founder of North of Byzantium and editor of Medieval World: Culture & Conflict.