The Mut Temple in Karnak and Egyptian temple collections

by Roberto A. Díaz Hernández

Introduction: a brief description of Mut’s temple

One of the many functions of an Egyptian temple was the preservation of cultural property and cultural memory through the collection of statues and sacred artefacts (see further Díaz Hernández 2017 and ibid. 2019: 33–34). Mut’s temple in Karnak is a suitable case study of Egyptian temple collections and treasures due to the hundreds of statues of the goddess Sekhmet found there in the 19th century and a scene featuring sacred artefacts on the east wall of Montuemhat’s crypt. The Mut temple is located south of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak which is linked to it by an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes. It is devoted to the goddess Mut - an Egyptian mother goddess usually represented as an anthropomorphic being with a human, or sometimes a lion’s, head (te Velde 1982: 246–247). Since the times of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut (1478–1458 BCE) Mut was part of the Theban triad as Amun’s female companion and Khonsu’s mother. Although she was worshipped in many places in Egypt, her most important cult place from the beginning of the New Kingdom (1539–1077 BCE) onwards was at Karnak.

The earliest archaeological evidence for Mut’s temple is its platform, discovered by the Brooklyn expedition in 1985 and dated to the reigns of Hatshepsut and her stepson Thutmose III (1479–1425 BCE) (Fazzini and Bryan 2021: 35–36). During that period a sacred lake called Isheru surrounded the temple on three sides. Later a large temple now referred to as Temple A, a ruined building referred to as Chapel B, a temple of Ramesses III, and Taharqa’s gateway were built around it. The whole area, known today as the Mut Precinct (see Fig. 1), attained its present size during the Ptolemaic period (Fazzini and Bryan 2021: 14).

Mut’s temple was further enlarged time and again after the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Montuemhat, 4th Prophet of Amun and Governor of Upper Egypt (see Fig. 7, below), rebuilt it under the Kushite pharaoh Taharqa (690–664 BCE) adding a small chapel or crypt for himself within the east wall of the temple. This chamber was decorated with biographical inscriptions and a scene featuring statues and sacred artefacts (see Figs. 8–10, below).

Figure 1. The Mut Precinct (@ Fazzini and Bryan 2021: 13).

The Sekhmet statues

Amenhotep III (1390–1353 BCE) ordered the production of hundreds of Sekhmet statues. According to Yoyotte (1980: 49–51), they were originally intended for his funerary temple at Kom el-Hettan on the West Bank of the Nile and they were dispersed through Egypt’s sanctuaries including Mut’s temple in Karnak at the beginning of Ramesses II’s reign (1279–1213 BCE). The reallocation of the Sekhmet statues may be related to the fact that Amenhotep III’s funerary temple stopped functioning from the 19th Dynasty onwards (1292–1191 BCE). Bickel (1993: 1–13) pointed out that building materials from Amenhotep III’s funerary temple were reused in Merenptah’s royal cult temple. It has also been suggested (Toonen et al. 2019: 196 and 204) that Amenhotep III’s funerary temple was destroyed by an earthquake at the beginning of Merenptah’s reign (1213–1203 BCE) which might be the cause of the reallocation of the Sekhmet statues through other Theban temples. At least 128 Sekhmet statues and statue parts of granodiorite, diorite and gabbro have been found hitherto in Amenhotep III’s funerary temple (Sourouzian et al. 2007: 331 and 2016). They probably came from different workshops for workmanship and material vary (Sourouzian et al. 2007: 333).

In the 19th century, 498 Sekhmet statues were still to be found in Mut’s temple. From their location and symmetrical disposition Mariette estimated that originally there were 572 (1875: 15 and Lythgoe 1919: 3). Most of these statues portray a sitting Sekhmet holding an ankh — the Egyptian symbol of life — in her left hand and wearing a sun disk on her head (see Fig. 2). Standing Sekhmet statues are less numerous than sitting ones and they feature a papyrus sceptre in the goddess’ left hand and an ankh in her right hand (see Fig. 3 and Fazzini/Bryan 2021: 41–42). Both types of statues were placed in a double row in two corridors along the east and west sides of the two colonnaded courts (Lythgoe 1919: 4). Although most of them have been dispersed through museums around the world (see the list in Gauthier 1920: 181–182), some Sekhmet statues still remain in Mut’s temple and they are displayed as in a museum (cf. Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 2. Sitting Sekhmet (2022. Neues Museum, Berlin, ÄM 7267).

Figure 3. Munich’s standing Sekhmet (State Museum of Egyptian Art, GL 67). By captmondo - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38740418.

Figure 4. Sekhmet statues in Mut’s temple (2019).

Figure 5. Sekhmet statues in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (@Lythgoe 1919: fig. 21).

Sekhmet statues frequently feature inscriptions with epithets usually applied to that goddess. One of them conveys the assimilation of Sekhmet and Mut probably due to the leonine character of both goddesses, which explains the presence of a great number of Sekhmet statues in Mut’s temple:

“(Sekhmet is the one) who is associated with Mut.”

(Germond 1981: 178–179 and Gauthier 1920: 191, N° 56)

According to Yoyotte (1980: 52–71), those statues constitute a “litany” to Sekhmet, for their epithets are the same as those found in inscriptions accompanying a series of Sekhmet statues carved on wall temples, such as those from Edfu, Dendera, Kom Ombo and Tod. There is no doubt that the Sekhmet statues fulfilled a religious and ritual function in Mut’s temple and it is likely that they were presented to the temple as royal tokens of gratitude for the goddess’s help in overcoming a difficult and dangerous situation. In fact, Greek and Roman authors mention donations of sacred artefacts and statues to temples as a thanksgiving after an illness (see for example Herodotus’ story about Pheros’ blindness, Hdt. 2, 111; cf. also Fazzini 1996, 134–135 and Díaz Hernández 2019: 38). In the same vein, rituals such as the Festival of the New Year or the king’s jubilee — called Sed festival — were performed before Sekhmet’s statues in order to appease the negative power of the leonine goddess (Bryan 1997: 60 and Draper-Stumm 2018: 5).

Along with their religious function, Sekhmet’s statues were also considered a collection of sacred artefacts by the Mut temple priests, for they materialised a meaningful system of sitting and standing statues used in rituals performed for the cult of that goddess. Moreover, Sekhmet’s statues belonged to the “cultural property” of Mut’s temple, whose priests were responsible for their preservation as well as for their decoration and attire during offering rituals, in the same way as religious statues and paintings are collected and preserved today in European cathedrals and churches, as for example St. Peter and Paul parish church in Görlitz, where sacred objects and paintings are displayed as in a museum (see Fig. 6). The Sekhmet statues were, thus, a complete temple collection of holy images that have been partly lost and partly integrated into other collections—today in private and public museums—in the course of history.

Figure 6. Tombstones in St. Peter and Paul parish church in Görlitz (2018).

The scene on the east wall of Montuemhat’s crypt

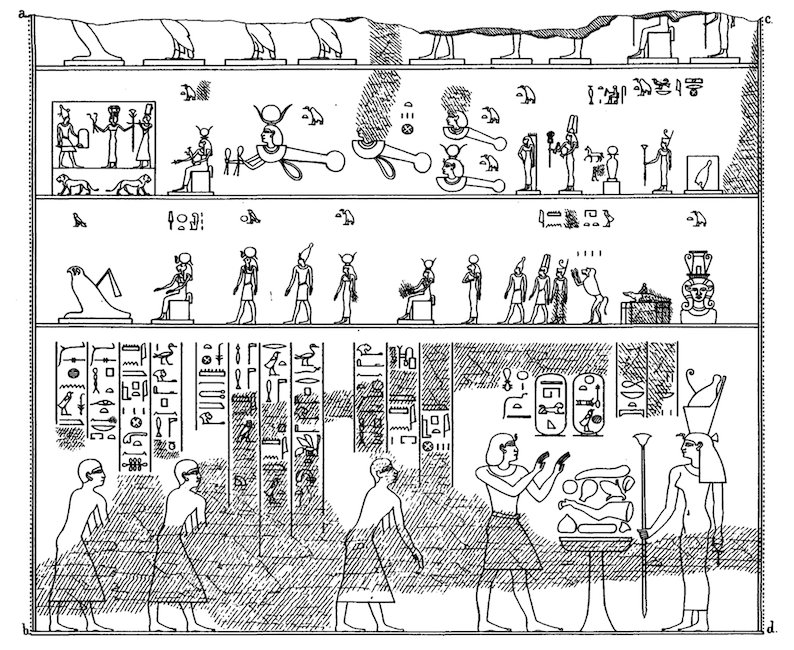

In the reign of Taharqa, Montuemhat, 4th prophet of Amun and governor of Upper Egypt (see fig. 7), carried out a rebuilding of the Mut temple, where he added a small chapel or crypt discovered by Mariette in 1859 (Fazzini and McKercher 2021: 37–38 and Fazzini and Bryan 2021: 41–42). This crypt (ca. 210 cm × 100 cm) had inscriptions on the door jambs and on the north and south walls as well as an offering scene featuring sacred artefacts on the east wall – the analysis of which now relies on Mariette’s copy and Wilbour’s 1881 notes (see Figs. 8 and 9) since most of the figures have faded away (see Fig. 10).

Figure 7. Montuemhat (2022. Neues Museum, Berlin, ÄM 17271).

Figure 8. The scene on the east wall of Montuemhat’s crypt after Mariette (1875: pl. 43).

Figure 9. Mariette’s drawing with Wilbour’s pencilled notes. Drawing published by Fazzini/McKercher according to the original disposition of hieroglyphics and figures (2021: fig. 4.4).

Figure 10. Today’s state of the scene on the east wall of Montuemhat’s crypt (2019).

The scene was divided into four registers (Leclant 1961: 231–238). Already in 1859 the upper part of the top register was lost so that only the lower parts of nine statues could be seen. The second register from the top features not only statues, but also sacred artefacts, such as four Mut menat necklaces with a human head, a heset vase and an Upper Egypt crown. These artefacts most probably belonged to the temple treasure kept in Montuemhat’s crypt (see Fazzini and McKercher 2021). A menat necklace was a ritual artefact used as an instrument during the performance of songs and dances (see Fig. 11 and Staehelin 1982: 52–53), and its appeasing and apotropaic power calmed down the fury of some deities. Heset vases were usual royal donations to temples for priests to use in libation rituals (see Fig. 12), and they were frequently made of valuable materials, such as gold and silver. The Upper Egypt white crown may have been a copy of the one worn by Taharqa. The third register features statues of gods and sacred animals, of which a baboon with the numeral 4 refers to the four statues preserved until today in Mut’s temple (see Fig. 9, above). The lowest register shows Taharqa offering and worshipping the goddess Mut.

According to Montuemhat’s biographical texts, the sacred artefacts and statues on the east wall of his crypt were depicted following a “great inventory” (sjp.t wr) which must have contained the whole cultural property of Mut’s temple. In fact, Egyptian temple inventories were expertise (that is technical) texts containing a description of the sacred artefacts kept in the treasure chambers of the temples, such as that described in Montuemhat’s crypt (Díaz Hernández, forthcoming), in the same way as valuable objects were preserved in the sacristies of medieval churches — a precedent of later cabinets of curiosities and today’s museum.

Figure 11. A New Kingdom menat necklace (The Metropolitan Museum of Art 11.215.450).

Figure 12. A New Kingdom heset vase (British Museum 43042).

Conclusion

The study of statues and sacred artefacts as items of material culture rather than just religious objects allows us to understand their actual material and symbolic value. Egyptian priests were responsible for the preservation and care of the cultural property housed in Egyptian temples. The study of the Sekhmet statues and of the sacred artefacts depicted in Montuemhat’s crypt gives us an idea of the material wealth treasured in Egyptian temples. Future research on temple collections should examine in more detail the objects recorded on temple inventories and occasionally found in favissae (votive pits), as for example the over 700 statues and 17,000 bronzes discovered by Legrain in 1903 in a favissa in Karnak (see Legrain 1905).

References

Bickel, S. 1993. Blocs d’Amenhotep III réemployés dans le temple de Merenptah à Goruna. Une porte monumentale, Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 92, 1–13.

Bryan, B. M. 1997. The statue program for the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III, in. S. Quirke (ed.) The Temple in Ancient Egypt, 57–81.

Díaz Hernández, R. A. 2017. The Egyptian temple as a place to house collections (from the Old Kingdom to the Late Period), The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 1–9.

— 2019. Der ägyptische Tempel als „Kulturgut“ nach Aussagen griechisch-römischer Autoren. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo 74, 33–42.

— forthcoming. Defining the concept of “Egyptian Temple Inventory”: The s:jp(.tj)-texts as an administrative text genre, in: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Congress of Egyptologists.

Draper-Stumm, T. 2018. Sekhmet statues from the reign of Amenhotep III in the British Museum and a formerly uncatalogued head fragment: a reassessment. The Antiquaries Journal 98, 1–15.

Fazzini, R. A. 1996. Bust from a statue of goddess Sekhmet, catalogue entry 65, in: A. K. Capel and G. E. Markoe (eds), Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven: Women in Ancient Egypt, 134–136.

Fazzini, R. A. and Bryan B. M. 2021. The Precinct of Mut at South Karnak. An Archaeological Guide.

Fazzini, R. A. and McKercher, M. 2021. The Montuemhat Crypt in the Mut Temple: A new look, in Y. Barbash and K. M. Cooney, The Afterlives of Egyptian History. Reuse and Reformulation of Objects, Places and Texts. In Honor of Edward Bleiberg, 37–54.

Gauthier, H. 1920. Les statues thébaines de la déesse Sakhmet, Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 19, 177–207.

Germond, P.1981. Sekhmet et la protection du monde.

Leclant, J. 1961. Montouemhat, Quatrième Prophète d’Amon, Prince de la Ville.

Legrain, G. 1905. Renseignements sur les dernières découvertes faites a Karnak. Recueil de travaux relatifs a la philologie et a l’archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes 27, 61–82.

Lythgoe, A. M. 1919. Statues of the Goddess Sekhmet. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 14, 3–23.

Mariette, A. 1875. Karnak, étude topographique et archéologique avec un appendice comprenant les principaux textes hiéroglyphiques découverts ou recueillis pendant les fouilles exécutées à Karnak par Auguste Mariette-Bey. 2 vols.

Sourouzian et al. 2007. The Temple of Amenhotep III at Thebes. Excavation and Conversation at Kom el-Hettân. Fourth Report on the Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Seasons in 2004, 2004–2005 and 2006. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 63, 247–335.

Sourouzian et al. 2016. Conservation work at the temple of Amenhotep III at Thebes, https://lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de/articles?nav_id=6722

Staehelin, E. Menit, in W. Helck and E. Otto (eds.) Lexikon der Ägyptologie IV, 52–53.

Toonen et al. 2019. Amenhotep III’s Mansion of Millions of Years in Thebes (Luxor, Egypt): Submergence of high grounds by river floods and Nile sediments, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 25, 195–205.

Velde, Herman te. 1982. Mut, in W. Helck and E. Otto (eds.) Lexikon der Ägyptologie IV, 246–248.

Yoyotte, J. 1980. Une monumentale litanie de granit. Les Sekhmet d’Aménophis III et la conjuration permanente de la déesse dangereuse. Bulletin de la Société Française d’Égyptologie 87–88, 47–75.

Online sources

Brooklyn Museum and the Precinct of Mut:

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/features/mut

L.I.S.A. Wissenschaftsportal Gerda Henkel Stiftung:

https://lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de/articles?nav_id=6722

Mut Temple. Brooklyn Museum Expedition to the Mut Precinct at South Karnak:

Roberto A. Díaz Hernández was born in 1982 in Salamanca, where he completed his licenciatura (master degree) in History in 2005, after which he got his Magister Artium diploma in Egyptology and Arabic Studies at the University of Leipzig (2009), and went on to do his PhD thesis on the language of Middle Kingdom biographical and literary texts under the supervision of Prof. Wolfgang Schenkel (2013) at the University of Tübingen. He worked as a postgraduate trainee at the Castle Museum in Jever (2013–2014), the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich (2015–2016) and the State Collections of Antiquities and Glyptothek (2016–2017) also in Munich, and as a research assistant in the Volkswagen-Project “Cosmogony and Theology of Hermopolis Magna” (2017–2018) at the Institute of Egyptology and Coptic Studies of the Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich, where he also taught Middle Egyptian until 2021. He is currently a Gerda Henkel Stiftung fellow working as a collaborator in the Qubbet el-Hawa Project (Jaén, Spain).