Parish of Wickford and Runwell: modern art in English churches

By Jonathan Evens

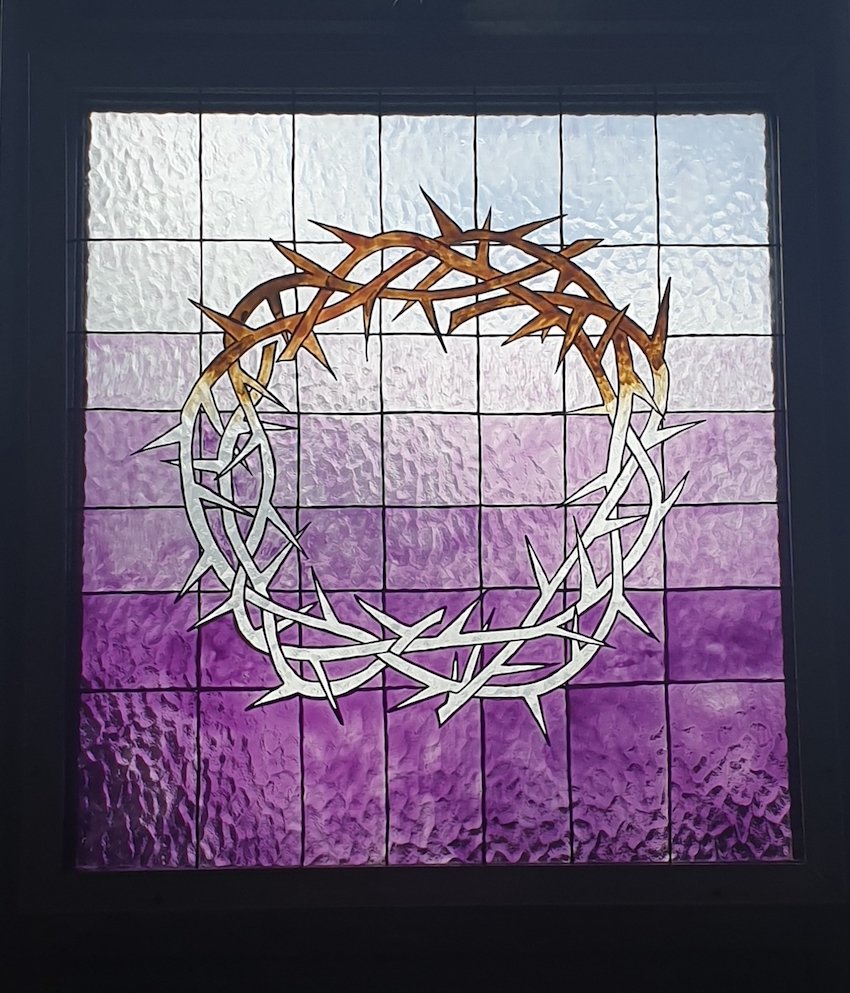

Stained glass window by Val Anthony at St Andrew's Wickford.

Introduction

The Wickford and Runwell Team Ministry, a parish of 40,000 people in Essex, was formed in 1981 from the Victorian St Andrew’s based in Wickford town centre, the 20th century St Catherine’s (historically the parish church) on the hill to the east of Wickford, and medieval St Mary’s to the north in the village of Runwell. Like many local churches, these three churches each contain interesting collections of art works from a range of periods and in a range of styles.

Exterior views of (from left to right) St Catherine’s, St Andrew’s and St Mary’s.

St Andrew's has stained-glass by local artists Val Anthony and Christine Daniels and banners by Julia Glover, plus a hidden painting by internationally exhibited artist David Folley. Folley's large 'The Descent from the Cross' is a major work by an artist who has exhibited widely across the UK and Europe, including at the Royal Society of Portrait Painters, in London, in Sweden and Germany, and at important contemporary international art fairs in Edinburgh and Dublin.

'The Descent from the Cross' by David Folley.

The reredos at St Catherine's was given to the church by the Vicar and Churchwardens of the famous Victorian London church, All Saints' Margaret Street. It is by William Butterfield, the architect of All Saints, and is said to be one of the finest of its kind. Additionally, on the West wall of the church is a small part of a wall painting, believed to have been salvaged from the previous building. The church also has a range of Victorian stained-glass windows, each with their own dedication, which range from the Madonna and Child to the Crucifixion and on to depictions of saints.

The inscribed cross by David Garrard at St Mary's Runwell.

The colouring of the screen at St Mary's and the murals on the one pillar in the south aisle date from the 1930s-1950s and were undertaken, by his sons, under the guidance of then Rector, The Revd John Edward Bazille-Corbin: see below. Other 20th century artworks in the church are the painting of St Peter and the crucifix below it, the large painting of 'The Baptism of Our Lord' by Enid Chadwick of Walsingham, and Stations of the Cross by local woodworker David Garrard which use the motif of the Runwell Cross. The Runwell Cross formed by four circles in a square, the instrument of our redemption set within a sign of the perfection of God, is to be found on the Prioress’s tomb, now located in the sanctuary of the church. Garrard also built an altar for the side chapel together with an inscribed cross on the side chapel wall.

Detail of the inscribed cross by David Garrard at St Mary's Runwell.

‘The Descent from the Cross’ by David Folley

David Folley is an English painter based in Plymouth. He paints subjects that range from abstracts, landscapes, seascapes, portraits, and race horses, including a life size painting of the famous British racehorse Frankel. He has completed portrait commissions for Trinity College Cambridge, and University College Plymouth and has had major commissions from Plymouth City Council and Endemol UK (a production company for Channel 4 television). He describes himself as “a twenty-first century romantic with a belief in the spiritual and redemptive possibilities of art.” Exploring the spiritual and redemptive possibilities of art is the foundation of his “romantic associations with the aesthetic tradition of Northern Romantic painting.”

The Revd Raymond Chudley, a former Team Vicar at St Andrew’s, knew Folley and had supported him in his artistic career. As an act of gratitude, Folley made this painting as a gift for Chudley when he got married, around the time he retired from parish ministry. The painting was too large for Chudley’s home, so was gifted to St Andrew’s and was dedicated by the Bishop of Bradwell in 1996.

'The Descent from the Cross' by David Folley in the Jesus Chapel at St Andrew's Wickford.

Folley’s friend Alan Thompson has described the work well. Thompson writes:

“David Folley has painted The Descent from the Cross, the melancholy depth of hopelessness, in a major work of heroic proportions. It is a large canvas painted traditionally to inspire the viewer to contemplate all that had culminated in what seemed at the time to be the final act of a tragedy. The viewer cannot share the utter despair of the participants in the painting because he or she knows what they didn't - that the body will be resurrected.

The way David has painted the body expresses the physical suffering Christ endured, whilst the dripping blood from the wound the soldier inflicted on Him, is shown as a rainbow. The explanation of this is that God told Noah that the rainbow was the sign of the new covenant with the earth. This is just one of many examples of Christian iconography illustrated in this work.

Mary, looking up at her son, is depicted as a modern provincial character in the manner we have associated with Stanley Spencer. Behind Jesus, Joseph of Arimathea, with a moustache, is painted in blue to denote spiritual love, constancy, truth and fidelity.

At the extreme right-hand side of the picture, the Revd. Raymond Chudley, who commissioned the painting, is shown in the traditional fifteenth century role of the donor, kneeling in prayer, with his attention fixed upon the body of Christ.

Facing him is the artist. He has included himself, portrayed as holding a broken spear as if to suggest that he had been responsible for the wound in the side of Christ. He is balancing precariously on a skull, a memento mori, signifying the transitory nature of life and also reading across to Calvary, which is derived from Golgotha, which is Hebrew for skull. He is also 'pregnant' with a foetus, which the artist sees as humanity giving birth to the Christ within, and transforming themselves into Sons of God rather than sons of man.

From the bottom of the painting is an outstretched arm, which just fails to touch Christ's hand, because the hand is withdrawn. This is intended to signify man's desire, through science, to explain the laws of the universe and so become almighty. He is almost there but cannot touch. There is a visual tension between God and man”.

Folley says, “I sum up this painting as being made up of a composite of the works of great masters of the past. Not copying them slavishly but developing my own concept of individualism with emphasis on vivid imagery, technical refinement, complex iconography and innovation.” Among the artists referenced are El Greco, Grünewald, and Donatello.

Reredos by William Butterfield

Reredos by William Butterfield at St Catherine's Wickford.

All Saints Margaret Street is a Grade I listed Victorian church in Fitzrovia, near Oxford Street, London. It is regarded as one of the foremost examples of High Victorian Gothic architecture in Britain. It was designed in 1850 by William Butterfield (1814-1900), an architect strongly associated with Gothic revival church building and the Oxford Movement. Completed in 1859, the red brick church was built around a small courtyard with an adjoining vicarage and a choir school. The interior is noted for its rich decoration and beautiful fittings – a true ‘hidden gem’ in the streets of central London.

The church owes its origins to the Cambridge Camden Society (from 1845, the Ecclesiological Society) founded in 1839 with the aim of reviving historically authentic Anglican worship through architecture. In 1841, the society announced a plan to build a ‘Model Church on a large and splendid scale’ which would embody important tenets of the Society:

· In the Gothic style of the late 13th and early 14th centuries

· Honestly built of solid materials

· Its ornament should decorate its construction

· Its artist should be ‘a single, pious and laborious artist alone, pondering deeply over his duty to do his best for the service of God’s Holy Religion’

Above all the church was to be built so that the ‘Rubricks and Canons of the Church of England may be consistently observed, and the Sacraments rubrically and decently administered’.

Butterfield designed nearly 100 churches and related buildings during his long career, including the chapels of Balliol College and Keble College, Oxford, and built in a highly personal form of gothic revival. All Saints Margaret Street remains his masterpiece.

Variegated brick banding and contrasting coloured materials are characteristic of all Butterfield’s works. Interior surfaces were covered with marble and tile to achieve an even richer coloration. Butterfield’s ‘structural polychromy’ became the fashion of the late Victorian period. The reredos now at St Catherine’s is in this style of polychrome ornamentation and different polished marble colours. Here, Butterfield has used grey, brown, green and cream marble to create floral designs within the double triform and intricately carved stone frame.

Murals at St Mary’s Runwell

Murals of St Peter and the crucifix by Anthony Corbin at St Mary's Runwell.

John Edward Bazille-Corbin (1887-1964), as mentioned above, became Rector of Runwell St Mary in 1923 and was to hold this benefice until his retirement on 30 September 1961. He was a fervent Jacobite, High Tory and devotee of the Sarum Rite, belonging to the High Church party and espousing Ritualism to the full. The present-day appearance of the church owes much to Bazille-Corbin who carried out many changes during his long incumbency.

Painted rood screen at St Mary's Runwell.

The colouring of the screen and the murals on one pillar in the south aisle date from the 1930s-1950s and were undertaken, by his sons, under the guidance of Bazille-Corbin to 'reproduce as closely as possible' the decoration of the medieval church. The painting of St Peter and the crucifix below it are by his son Anthony Corbin and are “restorations of medieval work which had been well and truly scraped out, but the traces of which could, at that date, still be faintly seen.”

'The Baptism of Our Lord' by Enid Chadwick

'The Baptism of Our Lord' by Enid Chadwick.

Enid Mary Chadwick (1902–1987) was a British artist known for religious art and children's religious material who lived in Walsingham for more than fifty years. She was the daughter of a priest, had attended a convent school in Oxford and trained at the Brighton School of Art prior to coming to Walsingham in 1934. Her paintings and her personal style appear in the Anglican Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham.

As Fr Charles Smith has noted, in her work “The mysteries of the faith, the lives and legends of the saints, are set before us in a way all can understand.” He notes, too, that “Her decoration is direct, and full of devotion” as “Behind all this and supporting it, was a life of deep and dedicated prayer … a matter of remaining quietly in the presence of God.” On her tombstone are found the words, ‘Lord I have loved the habitation of thy house’. Peter Kwasniewski has written that Chadwick’s work is “simple enough for young children, and yet at the same time full of complexities for those who are attentive.”

With its flat, outlined style and use of gold leaf, ‘The Baptism of Christ’ has the feel of an icon without having been written as a traditional icon. The composition sees Christ in the waters of the Jordan, depicted as equating to a cleft in the rock and, therefore, a reminder of God’s provision of water to the Israelites in the wilderness at the same time as showing us the banks of the river with water flowing between. Christ is framed by John Baptist on the left, angels on the right and above, the hand of God the Father and the dove of the Spirit. In this way, Chadwick has created a simple, yet unified design, centred on Christ and the significance of baptism as a doorway to faith. The painting was gifted to the church by Fr David John Silk Lloyd.

Art Trails

As the artworks in the Wickford and Runwell Team Ministry demonstrate, churches have for many years been significant patrons of the visual arts and contain important and interesting works of art. Despite this, churches like ours face a significant issue in publicising and promoting access to our churches and these works. The reality is that, on the whole, visitors are unlikely to travel to see a relatively small number of interesting artworks. The likelihood of many people coming to one of those churches to see the art is fairly slim – the art is interesting and so are the artists, but neither are especially well-known. Nor are any of the churches on a tourist trail. However, if the churches work together – as they are increasingly seeking to do - to publicise the art and to organise shared events to attract visitors, then the chances of bringing visitors to see the art increases considerably.

I first used this approach when Vicar of St John’s Seven Kings where I worked with a cluster of Anglican churches in Aldborough Hatch, Goodmayes and Seven Kings. These had works of art by some of the best local and national artists of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. St Paul’s Goodmayes had stained glass designed by William Morris and Sir Edward Burne-Jones, as well as windows by Leonard Evetts, the most prolific British stained glass artist of the 20th century, a Madonna and Child by the contemporary Roman Catholic artist, Jane Quail, and a contemporary series of Stations of the Cross by Henry Shelton. Shelton had also worked at All Saints Goodmayes, where he had engraved windows and a stained glass East window. St Peter’s Aldborough Hatch had a sculpture by Anthony Foster, a pupil of the sculptor Eric Gill, depicting Christ as the good shepherd, a Crucifixion by Leonard Wyatt, a member of the Free Painters Group, and a sculpture of the Woman of Samaria by Aberdeen-born artist Thomas Bayliss Huxley-Jones. St John’s Seven Kings had stained glass by C.E. Kempe & Co. Ltd. And Arts and Crafts artist Louis B. Davis, plus a contemporary West window by Derek Hunt.

Art competitions and workshops in the cluster led to exhibitions timed to feature as part of community festivals, and then to an Art Trail with a route for visiting each church in turn and highlighting artworks of interest in the four churches. Fr. Ben Rutt-Field, then Parish Priest of St Paul's Goodmayes, said: "So often people walk past churches and think it is just a plain building - they aren't aware of the beauty inside." Revd. Petros Nyatsanza, then Vicar of All Saints Goodmayes, said: "We hope that with the Trail, churches will be at the centre of the community and people will come in and have a look and actually read through the stories of Jesus." Events organised to assist in these aims, included guided tours, open days, art talks and sponsored walks.

The success of this approach led to the creation of an Art Trail for the Barking Episcopal Area within the Diocese of Chelmsford. The aim of this Trail was to raise awareness of the rich and diverse range of modern and contemporary arts and crafts from the last 100 years which can be found within churches and, in particular, the 36 churches featured on the Trail. The significant works of art in these churches, taken collectively, represent a major contribution to the legacy of the church as an important commissioner of art.

This Art Trail was researched and developed by artist and Fine Arts lecturer, Mark Lewis. A leaflet publicises the Trail and provides information about the featured artists and churches. The leaflet includes a map showing the churches featured on the Trail together with contact details, so that visits to one or more churches can be planned in advance. Lewis’ brief was to research commissioned art and craft in the Episcopal Area from the past 100 years. While in England stained glass is the dominant ecclesiastical art form, he was also concerned to show a diversity and variety of media and styles within the selections made. He highlighted works such as the significant mosaic by John Piper at St Paul’s Harlow, etched windows by John Hutton at St Erkenwald’s Barking, a Crucifixion mural by Hans Feibusch at St Martin’s Dagenham, and the striking ‘Spencer-esque’ mural by Fyffe Christie at St Margaret’s Standford Rivers. Churches with particularly fine collections of artworks included: St Albans, Romford; St Andrew’s Leytonstone; St Barnabas Walthamstow; St Margaret’s Barking; St Mary’s South Woodford; and St Paul’s Goodmayes.

He and I then created the Art of Faith walk produced by the Corporation of London with the support of the Diocese of London. This walk enables walkers to discover contemporary works of art in the City’s historic churches, including work by Henry Moore, Damien Hirst and Jacob Epstein. Many of the churches in the City were damaged by bombing during World War II, providing opportunities in the post-war reconstruction to engage with contemporary art. These artworks are by prominent modern artists such as Jacob Epstein, Patrick Heron, Damien Hirst, Henry Moore, John Skeaping and Bill Viola, as well as work by other reputable artists such as Thetis Blacker, John Hayward and Keith New.

Among the marvellous artworks to be seen on this trail are: Henry’s Moore’s circular altar and Patrick Heron’s kneelers at St Stephen Walbrook; Damien Hirst’s gilded bronze sculpture of St Bartholomew entitled Exquisite Pain(2006) at St Bartholomew the Great alongside Josefina de Vasconcellos’s sculpture of The Risen Christ (Vasconcellos also has work at St Paul’s Cathedral); Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water)(2014) and Mary (2016), located in the South Quire Aisle of St Paul’s Cathedral, are by internationally acclaimed artist Bill Viola and explore birth and death, while Hood: Mother and Child (1983) in the North Quire Aisle, was Henry Moore’s last major work; St Botolph Aldgate has a fibreglass sculpture, Sanctuary (1985), by Naomi Blake, a survivor of Auschwitz, and dyed fabric batik reredos panels by Thetis Blacker.

Conclusion

Modern and contemporary art is often not publicised by churches and not included in guidebooks, particularly if recently commissioned. People can’t come to see what they don’t know about, nor are they likely to come to see one work (unless it is of great significance), so enabling people to see several interesting artworks through an art trail, whilst also exploring other aspects of the heritage and current life of those churches, is more likely to attract visitors to church collections.

Such trails open up church art and heritage to those who might not otherwise appreciate them. If churches raise awareness of the rich and diverse range of modern and contemporary arts and crafts which can be found within them, then others will see that the collections of art in churches, taken collectively, represent a major contribution to the legacy of the church as an important commissioner of art.

Once people have been attracted to visit, there are also many ways to encourage them to reflect on the spirituality of the works and the space. Leaflets and apps can be used to give ideas for reflection or prayer, while pilgrimages enable guided reflections. This is the next step for us in the Wickford and Runwell Team Ministry. We have written a reflective tour leaflet for St Mary’s Runwell and will create equivalents for St Andrew’s and St Catherine’s. We are staging exhibitions, performance events and day conferences at St Andrew’s and are inviting schools and other groups to visit to see the art there. St Mary’s and its art is also being developed as a centre for contemplation and reflection.

Art trails provide a marvellous way to encourage visitors to engage with the diversity of art found in many churches, and open to all the spirituality inherent in such art. Seeking silence and stillness in a church and among its artworks is a spiritual exercise that all can explore, whether religious or of no faith. This is particularly so, where each artwork is accompanied by a reflection to help viewers engage spiritually and practically with stillness and prayer. By encouraging viewers to treat such trails prayerfully as though on pilgrimage, art trails enable visitors to uncover moments where the sacred inhabits the ordinary.

Links

Art of Faith: https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/assets/Things-to-do/art-of-faith-walk.pdf

Barking Episcopal Area Art Trail: https://www.chelmsford.anglican.org/uploads/Barking_Art_trail.pdf

Fr John Bazille-Corbin: https://san-luigi.org/2012/08/18/members-of-the-san-luigi-orders-the-most-revd-j-e-bazille-corbin/

William Butterfield: https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Butterfield

Enid Chadwick: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enid_Chadwick

Cluster Art Trail: https://joninbetween.blogspot.com/2010/07/new-church-art-trail.html and https://joninbetween.blogspot.com/2011/08/local-art-trail.html

David Folley: http://www.discover-folley.co.uk/

St Mary’s Runwell: A reflective tour of its art and architecture - http://wickfordandrunwellparish.org.uk/uploads/3/5/3/9/35392776/st_marys_reflective_tour.pdf

Wickford and Runwell Team Ministry: The Arts and Artists - http://wickfordandrunwellparish.org.uk/the-arts-and-artists.html

Jonathan Evens in Team Rector for Wickford and Runwell. He was previously Associate Vicar for HeartEdge at St Martin-in-the-Fields, where he developed HeartEdge as an international and ecumenical network of churches engaging congregations with culture, compassion and commerce. In this time, he also developed a range of arts initiatives at St Martin’s and St Stephen Walbrook, a church in the City of London where he was Priest-in-charge for three years, as well as supporting St Martin’s in its ongoing partnerships around disability and church. He has been ordained for nineteen years and in that time has had involvement in setting up: the Barking & Dagenham Faith Forum; commission4mission, an artist’s collective; and Seven Kings Sophia Hub, a support service for business and community start-ups. He is co-author of ‘The Secret Chord’ (Lulu, 2012), an impassioned study of the role of music in cultural life written through the prism of Christian belief, and writes regularly on the visual arts for national arts and church media including Artlyst, ArtWay and Church Times. Before being ordained Jonathan worked in the Civil Service forming partnerships to support disabled people in finding or retaining work.