The Prophet’s Mosque in Medina

By Adam Bursi

Relics have been a topic of debate among Muslims from the inception of Islam until today. As Anna Bigelow writes: “The acceptability of things—certain kinds of things or things in general—is contested among various schools of Islamic thought,” with some Muslim thinkers and groups classifying relic veneration as a form of idolatry or shirk [1]. Alongside such ideological currents, there has also long existed a variety of traditions of Muslims collecting and venerating the relics of sacred persons and places, leading contemporary scholars to speak now of “the historical reality of relics in Islam” [2].

The tension between these different Islamic positions is embodied perhaps nowhere as distinctly as at the Prophet’s Mosque (in Arabic, al-Masjid al-Nabawi) in the city of Medina in the western Arabian Peninsula. What began in the seventh century as a simple place of communal worship became, over the course of time, also a shrine and pilgrimage destination housing the bodies of the Prophet Muhammad and the first two caliphs, Abu Bakr and Umar. Moreover, the Mosque’s “collection” of revered objects extended beyond these graves to the building’s physical features—such as its columns and other architectural landmarks—which themselves became hallowed sites through their associations with the memory and practice of the Prophet and the primordial Muslim community. In a sense, the Mosque was itself structurally composed of a collection of sanctified objects and spaces. Traditions of visiting these people, places, and things in the Prophet’s Mosque emerged as acts of ritual piety throughout the centuries. Yet these practices have also been contested, as the question of how visitors should (and should not) interact with the Mosque’s “collection” has been provoked and reexamined.

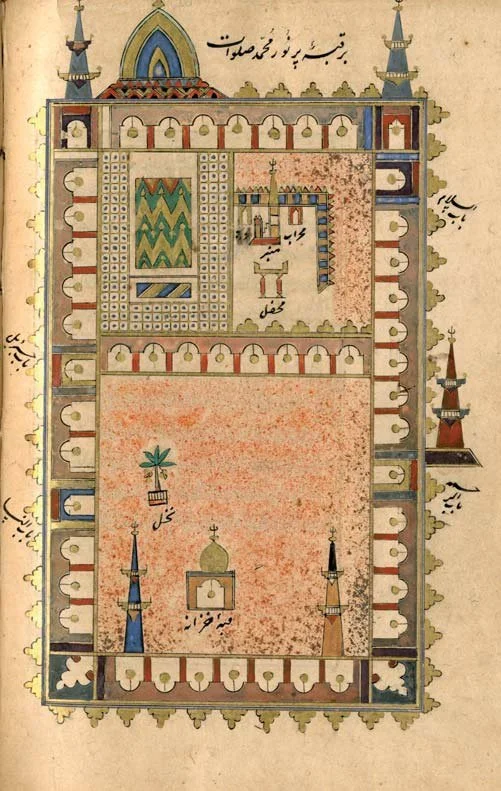

Figure 1. Illumination of the Prophet’s Mosque from a sixteenth-century manuscript. (Leiden University Library Or. 832, folio 113b)

According to Islamic tradition, the Prophet’s Mosque was initially built by the Prophet Muhammad and his Companions in 622 CE following the early Muslim community’s emigration (or Hijra) from Mecca to Medina. While the early structure was reportedly made of palm fronds and mud bricks, the Mosque was expanded several times in the years following the Prophet’s death in 632, including a monumental reconstruction in the early eighth century under the orders of the Umayyad caliph al-Walid ibn ‘Abd al-Malik. Architectural adaptations to the Mosque would continue throughout the centuries, but the Umayyad-era building remained an important touchstone for the space, in part because it was at this time that one of the most notable features of the building was implemented: the incorporation of the tomb of the Prophet Muhammad (and of the first two caliphs) into the Mosque structure. Located near the building’s eastern wall, the graves were sealed inside a walled tomb enclosure, and its placement there turned this part of the Mosque “into a shrine to the Prophet” [3]. In the thirteenth century, a wooden dome was constructed over the tomb; the dome was renovated over the years, eventually being covered in lead sheets and painted its distinctive green color in the nineteenth century.

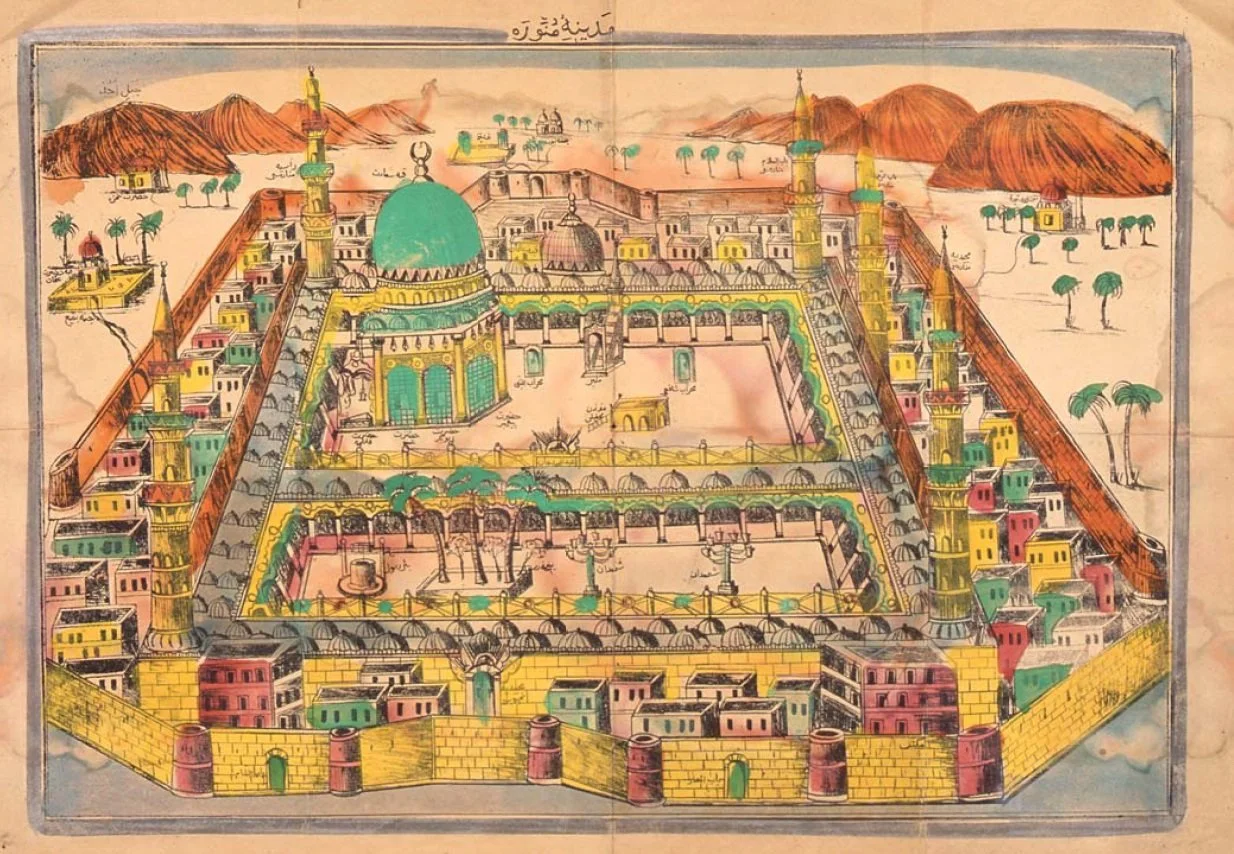

Figure 2. Nineteenth-century lithograph of the Prophet’s Mosque. (Leiden Museum of Ethnology RV-543-10)

The Prophet’s Mosque became a significant pilgrimage destination, as Muslims frequently came to combine the performance of the hajj to Mecca with visitation of Medina. The Prophet’s tomb was an important part of the Mosque’s sanctity, and a variety of devotional acts surrounding it emerged over the centuries. These actions ranged from visitors verbally greeting, touching, and praying beside the tomb—sometimes for extended periods of time—to casting letters of supplication to the Prophet through the grating into the tomb chamber [4]. Visitors’ descriptions of the tomb often mention the many perfumes that were used to scent the space around it. For example, in his travelogue, the twelfth-century Spanish pilgrim Ibn Jubayr narrates the walls as being “daubed with an unguent of musk and other perfumes to a depth of half a span, and blackened, cracked, and accumulated by the passage of time” [5].

While the tomb was (and continues to be) clearly a major component of the Prophet’s Mosque, the Mosque’s “collection” also extended beyond the resting place of the Prophet and his two Companions. The building has historically housed a collection of sacred sites and objects hallowed by tradition as the locations of events and/or practices from the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad. Even more such moveable objects once resided in the Mosque, prior to their relocation elsewhere by Ottoman-era authorities, as discussed by Simon O’Meara. Yet a variety of place-specific items have remained at the Prophet’s Mosque: indeed, object and space have often combined in these venerated locations of the early Muslim community’s sacred history.

An example is the Mosque’s mihrab: that is, the semicircular niche that directs Muslims’ prayers southwards in the direction of the Ka’ba in Mecca. While nearly every mosque has some form of a mihrab, this particular mihrab not only guides the direction of prayer for individuals—it also serves as a commemorative marker of the precise site where the Prophet is said to have prayed within the Mosque, thus monumentalizing the “memory of the charisma of the Prophet” [6]. Moreover, the mihrab was “at least for a part of its history, a repository of one relic of the Prophet” [7]. In his description of the Prophet’s Mosque, the tenth-century scholar Ibn ‘Abd Rabbihi reports that “in it [the mihrab] is the wooden stake (watad) upon which the Prophet would support himself when rising from prostrations” [8]. Thus, according to Ibn ‘Abd Rabbihi, a stick touched by the Prophet Muhammad was on display in the mihrab in the Prophet’s Mosque. Functioning as a remnant of the Prophet and housing another remnant within it, the mihrab thus seems to have acted as a sort of combined relic and reliquary for some period of time.

Figure 3. The Prophet’s Mihrab in the modern mosque. (Image courtesy of the Madain Project) Mehrab of the Prophet (Mihrab Nabawi) - Madain Project (en)

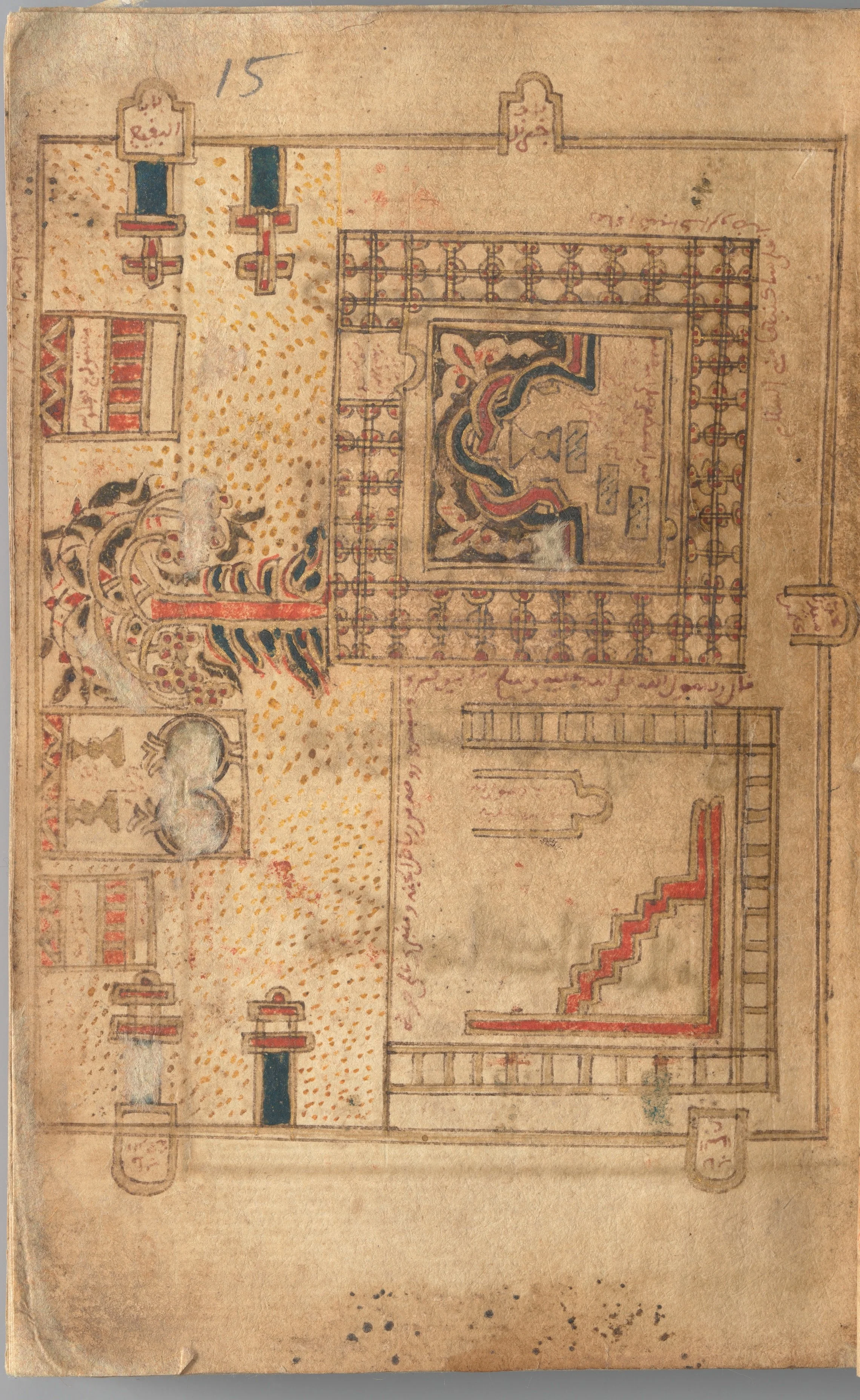

Another important object located at the front of the Mosque was the minbar, or pulpit, that the Prophet Muhammad had stood upon when delivering sermons. A tradition found in a tenth-century Shii text gives an idea of the ritual activities surrounding this relic: “When you are finished praying beside the Prophet’s tomb, go to the minbar and touch it with your hand. Grasp both of its pommels and then wipe your eyes and face, for it is said that it is a healing for the eye. Then stand beside it, praise and extol God, and request from Him what you need” [9]. It was not only Shii visitors who venerated the minbar in this way, as Sunnis are likewise recorded touching the minbar for blessing and praying beside it [10]. Ibn Jubayr, for example, records that during his visit to the mosque, a board had been placed over the seat of the pulpit so that it could not be sat upon, but “men insert their hands beneath [the board] and smooth the venerated seat to acquire blessings by touching it” [11]. The minbar was so important a relic that stylized images of it frequently appear—alongside the Prophet’s tomb—in the illuminations in Islamic devotional manuscripts. [12]

Figure 4. Illumination of the interior of the Prophet’s Mosque from a seventeenth-century manuscript, with the Prophet’s tomb represented at the top and the minbar at the bottom. (New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017.301) https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/752280

Other important pieces in the Mosque’s “collection” of sacred objects included several of the pillars inside the building. In a number of cases, individual columns were associated with events from the time of the Prophet Muhammad and the early Muslim community. Such associations allowed these objects to function as “sites of memory” for Muslims’ communal history, and in some cases led to devotional rituals at the columns. One notable example is the “Perfumed Column”—so-called because it was coated in a saffron-based aromatic paste, perhaps as a way of distinguishing it from other columns—which is remembered as the column that stood closest to where the Prophet Muhammad would himself stand for ritual prayer in the Mosque [13]. Because of this Prophetic association, the Perfumed Column was cited as an efficacious location for performing divine petitions. Among other significant columns in the Mosque, one was associated with the words of the Prophet’s wife Aisha, and another was remembered as the spot where the Prophet would sit to receive delegations coming to visit him and embrace Islam. In the contemporary Prophet’s Mosque, the columns themselves are visually labelled with text so that visitors can easily identify which column is which.

Figure 5. The Pillar of Aisha in the modern mosque, with textual medallion identifying it. (Image courtesy of HajjUmrahPlanner.com)

The Prophet’s Mosque has stood as a site of continuity, even as things have changed within and outside it. Over the centuries, the Mosque’s collection has often been modified and updated—whether by choice, or due to destruction from natural forces like fire. The tomb complex has been maintained, despite occasional calls for its flattening from iconoclastic voices over the last century [14]. Debates have intermittently sprung up over how to engage appropriately with the Mosque’s collection of objects and spaces. Pilgrims’ pious acts of touch at the Prophet’s tomb, minbar, and elsewhere have historically drawn unease from some Muslim jurists [15]. Yet even with these questions, Muslims have continued to visit and venerate the Mosque and the sites within it. The Prophet’s Mosque continues to be considered one of the most sacred of Islamic spaces, itself made up of a collection of many smaller sacred places that have been long remembered and valued by the Muslim community.

Notes

[1] Anna Bigelow, “Introduction: Thinking with Islamic Things,” in Islam Through Objects, ed. Anna Bigelow (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), 12.

[2] Josef W. Meri, “Relics of Piety and Power in Islam,” in Relics and Remains, ed. Alexandra Walsham, Past & Present Supplement 5 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 98.

[3] Harry Munt, The Holy City of Medina: Sacred Space in Early Islamic Arabia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 106.

[4] Marion H. Katz, “The Prophet Muḥammad in Ritual,” in The Cambridge Companion to Muḥammad, ed. Jonathan E. Brockopp (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 150–53.

[5] The Travels of Ibn Jubayr, trans. Ronald J. C. Broadhurst (London: Jonathan Cape, 1952), 199.

[6] Heba Mostafa, “Locating the Sacred in Early Islamic Architecture,” in The Religious Architecture of Islam. Volume I: Asia and Australia, ed. Hasan-Uddin Khan and Kathryn Blaire Moore (Turnhout: Brepols, 2021), 15.

[7] Estelle Whelan, “The Origins of the Miḥrāb Mujawwaf: A Reinterpretation,” International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 18 (1986): 216.

[8] Ibn ʿAbd Rabbihi al-Andalusī, al-ʿIqd al-farīd, ed. Mufīd Muḥammad Qumayḥa et al., 9 vols. (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 1983), 7:289.

[9] Muḥammad b. Yaʿqūb b. Isḥāq al-Kulaynī al-Rāzī, al-Kāfī, ed. ʿAlī Akbar al-Ghaffārī, 8 vols. (Tehran: Dār al-Kutub al-Islāmiyya, 1388–1389 AH [1968]), 4:553.

[10] Adam Bursi, Traces of the Prophets: Relics and Sacred Spaces in Early Islam (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024), 198–99.

[11] Travels of Ibn Jubayr, 200.

[12] Hiba Abid, “Material Images and Mental Ziyāra: Depicting the Prophet’s Grave in North African Devotional Books (Dalāʾil al-Khayrāt),” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1 (2020): 331–54.

[13] Ghazi Izzeddin Bisheh, “The Mosque of the Prophet at Madīnah throughout the First-Century A.H. with Special Emphasis on the Umayyad Mosque” (PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 1979), 141–42; Mattia Guidetti, In the Shadow of the Church: The Building of Mosques in Early Medieval Syria (Leiden, Brill, 2017), 153.

[14] Ondřej Beránek and Pavel Ťupek, The Temptation of Graves in Salafi Islam: Iconoclasm, Destruction and Idolatry(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), 139, 144, 149, 179, 187.

[15] Beránek and Ťupek, Temptation of Graves, 27, 28, 42, 48, 54, 160; Bursi, Traces of the Prophets, 166–68, 196–200, 214–15.

Adam Bursi works on the editorial team at Fortress Press in Minneapolis. His research examines early Islam in dialogue with other late antique religions, focusing on the ways that holy objects, places, and stories contributed to the formation of early Muslim communities and identities.